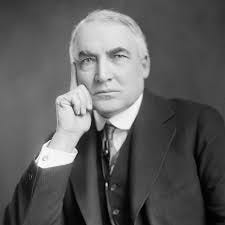

“In 1920 Warren Harding won America’s presidency promising a ‘return to normalcy’, following the first world war and the flu pandemic in 1918-20. A century on, his goal sounds more appealing than ever. It also looks frustratingly hard to achieve.” So opens a July 3 article from The Economist, which examines the current state of the economy in 50 countries, representing 76% of the world’s population and 90% of its GDP. The Economist asks the question “To what extent has the global economy ‘returned to normal’, that is to pre-Covid levels and patterns of economic activity?”. This seems like an appropriate follow-up to my post yesterday on the same subject (“The Economic Recovery: Finally some good news”), so I bring to your attention both The Economist article and another by Paul Krugman, cited below.

As you would expect, the answer to The Economist’s question is different for each country studied. Using an index of 100 for the level of pre-pandemic activity, measured across different economic sectors (travel, leisure, commercial), The Economist finds that the global index fell to a low of 33 and has now rebounded about half to an average of 66. But the level of recovery varies greatly by country. The US economy is now at 73, in line with the EU (71) and Australia (70) and a bit ahead of Britain (62), but well behind Hong Kong (96) and New Zealand (88). But a number of countries have not recovered nearly so much, and some that had recovered quickly are now regressing due to renewed outbreaks of Covid. Malaysia for example has recently fallen from 55 to 27 and Chile has again locked down its capital Santiago despite a vaccination rate approaching 80%.

The extent of recovery also varies by economic sector of course. Global in-person retail traffic is back to 90%, and office occupancy and public transit are back to 80%, but air traffic is still down at 30%. Remember that these are global averages, and patterns in the US may be different, for example in air traffic which is booming in the US.

What should we make of all this? I’m not entirely sure, other than to note that the US remains part of a global economy and our progress back to normalcy will to some extent be impacted by changing conditions in other countries, at least in some sectors (international air travel for example). More importantly, perhaps, I would caution us all to resist the temptation to extrapolate to the global economy our anecdotal observations about local activities in the US. The fact that Americans are or are not back eating in restaurants does not really tell us very much about the state of the global economy, although it might tell us something about consumer spending in the US (a large sector of the domestic economy).

For those of you behind The Economist’s paywall, you can read more here: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/07/03/our-normalcy-index-shows-life-is-halfway-back-to-pre-covid-norms

Picking up where The Economist leaves off, Paul Krugman in today’s NY Times addresses the question of how the US economy might change following the relaxation of Covid restrictions, what he calls our “medically induced coma”. Post Covid, what will the “new normal” look like here in the US?

Reasoning by analogy to the birth of the American Republic, and specifically to Alexander Hamilton’s push to support infant domestic industry with protective tariffs, Krugman expects that while much of the US economy will in fact bounce back rather quickly to pre-pandemic levels and patterns of activity, there will be some more permanent changes to the economy, of which the shift to remote working is just one notable example. Some of these more permanent changes, including a reduced labor force participation rate among older workers and two-income families, will likely reduce GDP by some amount. But in Krugman’s view this may well be a positive thing, and I think it is important that we understand his reasoning.

Quoting Krugman: “So the post-Covid-19 economy will look different from what we had before: There will probably be a glut of office space, and total employment will probably be a bit lower — Goldman Sachs estimates by around one million — than it would have been otherwise, because of early retirement. But these changes will, on the whole, be good things: The pandemic was deadly and costly, but one small compensation is that it gave us a chance to think, work and live differently.

Many people will disagree with Krugman about how to interpret or value these changes and you may as well. (Disagreement with Krugman seems to be a notable feature of some political commentary.) But we should resist the instinct automatically to equate GDP with the health of our economy, let alone the quality of our lives. As Krugman says: “The purpose of the economy isn’t to maximize G.D.P.; it is to make our lives better…And though the increased life satisfaction some people get by retiring early and spending more time at home actually comes at the expense of G.D.P., it makes the nation richer in what matters.”

We all want richer lives. And there are some good things that will have come out of the Covid experience. Perhaps the Covid shutdown has given us a once in a lifetime opportunity to figure out what we mean by “richer lives”, individually and collectively. Let’s not waste this opportunity.

Quoting Hamilton (the play, not the man), How lucky we are to be alive right now! If you don’t get this last reference (“how lucky we are…”), listen here: