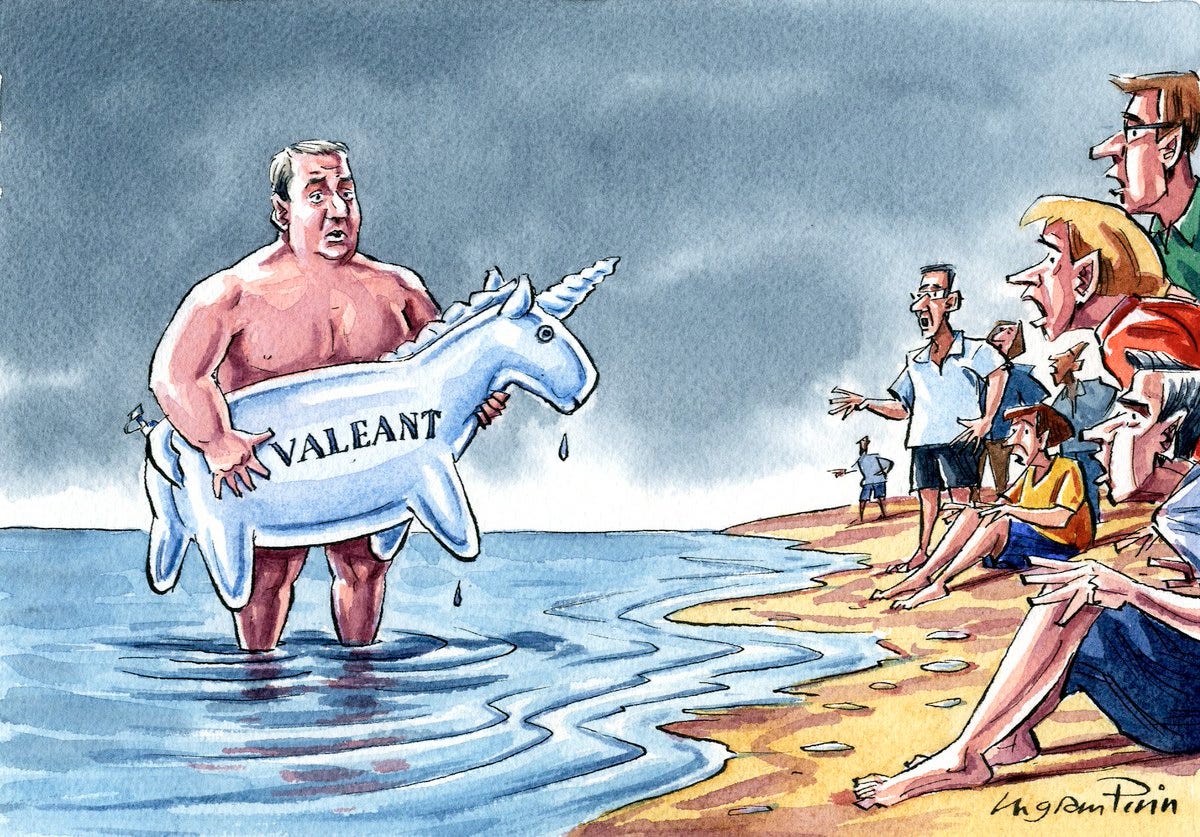

About six weeks ago I published the first installment of my “Swimming Naked” posts, which proved to be quite popular, due no doubt to the somewhat risque title. In it, I opened with a famous Warren Buffett quote about investor speculation and bear markets: “It is only when the tide goes out that we see who has been swimming naked”. And I suggested that when this happens, the results will not be pretty.

Since then, the US stock market has fallen further, despite one or two dead cat bounces. The S&P is now down 20% or so for the year and the Nasdaq is off about 30%. The Fed has again increased interest rates and has signaled several more moves to come. Ten-year UST bonds now yield over 3%, double the yield of a year ago. May CPI was up 8.6% year on year, and other inflation indices are also up strongly in both the US and abroad. Gas prices hit an all-time high. There are still roughly two job openings posted for every person unemployed, but hiring has started to slow and recession risk is now on the minds of investors, corporate executives and economic policy makers. Some think that stagflation may again become a reality in the US, for the first time since the 1970s. Suffice it to say that the financial tide has moved out quickly and strongly.

So what has the falling tide revealed?

Quite a lot actually. Here are just a few examples of the wreckage washed up on shore, with the tide still going out and likely more to come.

Tech stocks. Value matters, even for growth stocks, and if we didn’t know this before we do now. QQQ, the Nasdaq 100 index of mostly large cap tech stocks, is down 30% year to date, and tech stocks may have further to fall. During the financial crisis the Nasdaq fell over 40% and in the dotcom crash at the turn of the millennium it lost over 75% of its value (price). The market’s recent valuation adjustment of tech stocks, and growth stocks more broadly, is in part the predictable result of moving from a “risk on” to a “risk off” investment environment, with increased risk premiums demanded by investors. But the big drop in equity valuations also reflects the impact of rising interest (and discount) rates, particularly on the shares of companies whose earnings and cash flow will mostly be realized many years into the future, as well as the reevaluation of forecasted future cash flows for companies facing short-term business challenges and slowing growth, including the reversal of unsustainable covid-driven business trends. Netflix and Peloton, for example, are each down by over 70% this year, reflecting pretty much all of these various valuation drivers.

Meme Stocks. The classic meme stock beneficiary, Robinhood Markets (HOOD), is off 50% YTD and almost 80% LTM. But this still leaves the company with a market cap of over $6.5 billion, despite the dramatically changed investment environment, the proclivity of HOOD customers to trade in highly speculative and increasingly out-of-favor instruments (including crypto) and the SEC working to shut down payment for order flow (which accounts today for 80% or so of HOOD revenues). And $6.5 billion is a lot to pay for a company which has not yet demonstrated that it can earn a profit, even in boom years like 2021.

Crypto. Crypto has crashed, along with the wealth and dreams of many individuals who bet large amounts of money on various get-rich-quick Ponzi schemes (or pump and dumps) promoted by digital scam artists. Bitcoin and its progeny were billed by their promoters as “digital gold”, supposedly providing investors with protection against the inflation of fiat currencies. With inflation where it is today, this should be crypto’s moment to shine in the sun. But what we are seeing instead is the ugly underbelly of crypto, a place where the sun don’t shine. Bitcoin is down over 70% from its November 2021 high and TerraUSD—ironically a so-called “stablecoin”—has lost essentially all of its value. Crypto as a whole has lost two-thirds of its market cap, erasing $2 trillion of market “value”. So much for crypto as an asset class. More broadly, the collapse of crypto also calls into question the fundamental underpinning all of decentralized finance (DeFi), which many thought would be the wave of the future but instead turns out to have been a financial tsunami. Look for example at crypto lender Celsius Network—a firm built on layers of financial risk which would be unacceptable in any traditional financial institution today. For those of you who are not yet prepared to call it quits on crypto, who believe that the crypto winter will soon be over I encourage you to read this piece by the WSJ’s James Macintosh, The Fires Burning Behind Crypto’s Meltdown.

SPACs. Over 10% of all post-merger SPACs (those SPACs that have merged with operating companies) have received “going concern qualifications” in their 2021 audited financial statements, in some cases just months after completing their merger transactions. Companies receive going concern qualifications when their auditor believes there is a substantial doubt as to the company’s ability to stay in business for the next twelve months. This generally happens because of high cash burn rates relative to the amount of cash and other liquid assets on the balance sheet, doubts about the company’s ability to raise additional financing, and/or material adverse developments in the company’s operations (loss of key customers for example). A going concern qualification does not mean that a company will necessarily go bust, or do so within the next twelve months, and even bankrupt companies often stay in business under new ownership and with new capital structures. However ten percent is more than twice the proportion of going concern qualifications among the universe of companies which have gone public via traditional IPOs. This should shake the confidence of any investor who bought into SPACs in reliance on the transaction related due diligence supposedly done by sponsors and their other funding sources, the so-called “smart money”.

Softbank Vision Fund. I have written before about Softbank and its $100 billion Vision Fund, although apparently not under the banner of Banking & Beyond. Suffice it to say that I am a skeptic. I have never bought into the hype associated with Softbank founder Masayoshi Son and I have been a harsh and vocal critic of Softbank’s Vision Fund, which has an underwhelming list of investees (mostly lenders, not investors) and some questionable people at the helm (including former Deutsche Bank derivatives traders turned wannabe venture capitalists). In May, Softbank reported a $29 billion loss from investments for its fiscal year ended in March, mostly from mark to market valuation changes in its VC portfolio. This is a lot of money to lose in one quarter, even by Deutsche Bank standards, and the stock market has now wiped out almost half of Softbank’s cumulative investment gains since the inception of the Vision Fund.

Leveraged Funds. As the bull market in stocks entered its final phase back in 2020, investors piled into leveraged equity ETFs and were at least initially rewarded quite handsomely for doing so. But of course what goes up can and generally does go down, and leverage only accelerates the speed and extent of the reversal. And so for those investors who chose to get on board the leveraged equity roller coaster, their thrill on the way up in 2021 has now turned into a steep and stomach churning plummet down, causing more than a few investors to lose their lunch. But it seems that leveraged fund investments are not solely the preserve of aggressive equity investors. Fixed income investors searching for yield have also jumped on board, including in the muni bond market—historically the investment vehicle of choice for wealthy widows and others with low stated risk tolerances. And with interest rates rising quickly, these folks too must be feeling a bit queasy right about now.

Convertible Bonds. Converts are supposed to provide investors with both a leveraged play on equity upside and downside protection if the price of the underlying shares does not perform. But this hasn’t been the case so far in 2022, with the price of converts down 20% or so this year, more or less in line with the overall stock market Why is this? Well, first of all the issuers of converts tend to be relatively high risk companies, the share prices of which have fallen by more than the market this year. And so the strike (exercise) price on many outstanding convertible securities is now way out of the money, which reduces the intrinsic value of the equity call option embedded in the converts. (In contrast, higher volatility and increased interest rates increase the value of equity call options, offsetting some of the impact of reduced intrinsic value.) Also, interest rates and bond yields are up and so the price of the bond component has fallen as well. (Bond yield up, price down.) Add to this the increased risk of default at many convert issues, plus reduced liquidity in the convert market, and there you have it.

Endowment Funds. The portfolio managers of university and other endowment funds generally had an outstanding year in 2021, with their public equity portfolios up 25-30% and their private equity and venture capital investments up twice that. And no doubt more than a few of these folks collected big bonuses in recognition of their apparent investment prowess during the year. But for many, the gains of 2021 have now been largely erased by the market downturn in the first half of this year. And for their sponsoring (beneficiary) organizations, donor contributions are likely to be squeezed going forward and high cost inflation will put further pressure on covid-ravaged organizations who were already having trouble making ends meet.

Pension Plans. Like endowments, pension plans also had a great 2021, with equity markets up strongly and interest (discount) rates stable and low. But all that has changed during the first months of 2022. The data isn’t out yet (to my knowledge), but it is reasonable to expect that pension funds will also have been hurt by the big correction in equity and fixed income markets during the first half of this year. And to compound the pain, the forecasted nominal amount of future benefit payout obligations will have increased with inflation now running near record levels. But there is one silver lining in this generally dark cloud, which is the favorable accounting impact on pension funding estimates resulting from increased interest rates, which will reduce the present value of any given stream of future nominal cash flows (benefit payouts). To combat falling returns, a number of public pension plans have adopted policies which allow them to borrow money to leverage their investments, which works for the funds in up markets but against them in bad markets. (See Leveraged Funds, above). How these various factors will balance out over the course of the year remains to be seen, but pension plans which were substantially underfunded going into 2021 may well find themselves back deeply in the red despite last year’s big gains.

Russia Defaults. Russia defaulted on its foreign debt for the first time since the Russian revolution, due to the impact of increasingly stringent western sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The sanctions have largely blocked Russia from access to the global payments system, tightened last month by action of the US Treasury intended to cut Russia off from foreign investment, which means the latest debt payments made by Russia have not made it into the bank accounts of investors. Russia’s foreign debt is not large relative to the country’s GDP (even now) and Russia has plenty of dollar revenue to make the payments. This default has been expected by the markets for quite some time, with Russian foreign bonds trading at just pennies on the dollar prior to the default. This latest default by Russia is not expected to have significant long-term financial consequence for Russia. Russia last defaulted on its domestic debt in 1998, one of the events which triggered the infamous collapse of US hedge fund LTCM.

The Fed’s Reputation. One of the many books about the Fed which I have read over the years is David Wessel’s In Fed We Trust. By memory, this was a generally positive account of how US policymakers, most notably the Fed, bravely and successfully responded to the events of 2007-8, which Wessel called “The Great Panic” and which we today know as the Global Financial Crisis. But if Wessel were to rewrite his book today, I suspect that he might want to add a question mark to the title: In Fed We Trust? Until very recently, the Fed has been held in generally high regard by most of the public (although this hasn’t kept many voters from supporting Rand Paul). Alan Greenspan ran the Fed for 19 years during which time he became known as “the Maestro” (the title of Bob Woodword’s hagiography). Ben Bernanke was Fed chair during the events of 2008 and was widely praised at the time for having saved us from another Great Depression. And until recently many people also lauded current Fed Chair Jay Powell for working with Treasury and Congress to stabilize the US economy during the darkest days of the covid pandemic in 2020. But with capital markets crashing all around us and US inflation now running at near-record levels, this bloom has definitely come off the Fed’s rose. It would be wrong to say the Fed’s reputation now lies in tatters—I think it is still better than that of the Supreme Court, this week at least—but the Fed’s reputation has definitely taken some bit hits recently. As an organization the Fed is not without its faults, some of them intentionally built into the Fed’s charter, and the individuals running the Fed have no doubt failed from time to time and occasionally quite spectacularly. The US and global economy is in a very difficult position right now and the reasons for this are legion, with lots of blame (and more than a bit of bad luck) to go around, including at the Fed. But rightly or wrongly the world is looking to the Fed to lead the US out of this mess, however painful that may be. And if we lose confidence in the Fed, or the Fed loses confidence in its ability to respond to this latest crisis, I think we are all doomed.

In Conclusion. In drafting this post, I have had running through my head the lyrics to a song which I think is somehow appropriate to today’s topic, so let me share it with you in lieu of closing comments. The song is Mark Knopfler’s Beachcombing (sung with Emmylou Harris) and here are the opening lyrics:

They say there's wreckage washing up

All along the coast

No one seems to know too much

Of who got hit the most

Nothing has been spoken

There's not a lot to see

But something has been broken

That's how it feels to me

And this is in fact how things feel to me.