This post has been revised since it was initially published, including the addition of new links, some of which may have been published after the initial version of the blog was posted.

Setting the stage. For the most recent fiscal year (which ends September 30th), the US government granted students and their parents approximately $125 billion of direct financial support to pay for higher education expenses, consisting of $30 billion in grants (almost entirely Pell grants) and another $95 billion in federal student loans. The loans were issued to students (and the parents of students) who attended vocational training programs and community colleges, public and private undergraduate universities, and various graduate and professional degree programs. The loans were offered through several federal student loan programs, in varying loan amounts, some explicitly subsidized and some not. The interest rates on recently issued federal student loans range from 5% to 7.5% (plus fees), with interest accrual and repayment terms varying by the type of loan.

The US government’s current student loan portfolio has a face value (nominal amount) of around $1.6 trillion (as of June 30, 2022) and comprises the unpaid balance owed on loans going back at least 25 years, to 1997. (A surprising number of borrowers still owe student loan debt well into their retirement years.). Another $150 billion or so of outstanding student loan debt was issued pursuant to private student loan programs, some with federal guarantees issued pursuant to now defunct government programs and the balance of which are generally more expensive than federal loans and often require third-party (often parental) guarantees. The outstanding federal loans will for the life of the loans remain on the balance sheet of the US government, which is prohibited by law from selling or securitizing them (unlike lenders in the private market). (Note: There is an active secondary market in securitized student loans—Student Loan Asset Backed Securities, or SLABS—which consists primarily of privately issued student loans guaranteed by the federal government under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP), which was discontinued back in 2010.)

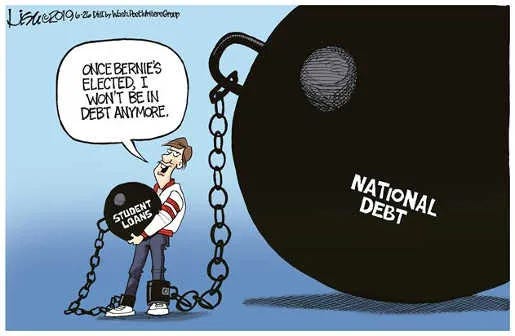

Politicians, educators and others have for years debated the structure and public policy merits of the US federal student loan program, a debate which has grown in intensity with the announcement a month ago of the Biden-Harris Student Debt Relief Plan. The Biden-Harris Plan proposes to cancel outright a significant portion of the total outstanding federal student loan debt, accounting for an estimated 25% or so of the face value of all student loan debt and as much as 100% of the debt owed by half the total number of borrowers. Biden-Harris also proposes to reduce significantly the future repayment burden on qualifying borrowers participating in federal income-based repayment plans (IBRPs), by raising the level of ‘discretionary income’ on which loan payments are based, reducing the mandated payment share of income from 10% to 5% and cancelling all remaining debt (including unpaid interest) at the end of 10 years instead of 20 years as under current plans. (I wrote about Biden-Harris in my last post, which you can read here.)

And so perhaps now is a good time for us to dig a bit deeper into the economics of the federal student loan program, focusing on the profitability of the program and the amount of taxpayer subsidy embedded in the current loan portfolio, which may impact how we think about the federal student loan program as well as the current public policy debate triggered by Biden-Harris Plan.

Was the US federal student loan program profitable before Covid and Biden-Harris? Back in 2013, Senator Elizabeth Warren described as ‘obscene’ the profitability of the US federal student loan program. That year, the Department of Education (DOE) reported that the US federal student loan program had generated an annual profit of $50 billion on a loan portfolio with a face value of around $1 trillion. This represented a 5% or so pre-tax return on assets (before administrative costs), which may or may not have been ‘obscene’ but was certainly healthy compared to the profitability of the consumer banking industry, which at the time probably generated an aggregate NIM (net interest margin = net interest income/interest earning assets) of around 3%.

But that was back in 2013, and we have good reason to believe that the profitability of the federal student loan program has declined markedly since then, and particularly in the last several years.

The GAO Report. In July 2022, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) issued its revised calculation of the expected profitability of the federal government’s outstanding student loan program. The GAO reduced its previous estimate of a $100 billion profit (‘negative subsidy’ in government accounting terminology) to a $200 billion loss (‘positive subsidy’). Almost 40% of this $300 billion revision was attributable to structural changes in the federal student loan programs, most notably the covid-related payment moratorium initiated under the Trump Administration and continued (and extended) under Biden. The balance came from revised downward estimates of future revenues from student loan payments, attributable to a number of factors including higher than expected credit losses and an increased number of borrowers participating in subsidized (reduced payment) income-based repayment plans. And all of this was before any anticipated impact from the Biden-Harris Plan.

The GAO’s analysis was conducted in line with conventional (and legally mandated) government accounting standards, but there is reason to believe that the GAO may actually have understated the size of the economic loss (subsidy) embedded in the federal student loan portfolio. Using its own present value methodology, the GAO discounted its revised estimates of future cash flows (borrower payments) to present value at a discount rate equal to the government borrowing rate, at the time 2%. But while 2% may have been the right rate to use in measuring the government’s actual cost of funding (eg for calculating NIM), it may not be the right rate to use for calculating the economic present value of a risky student loan portfolio.

To restate the obvious, in the federal student loan program the US government is the lender not the borrower, and it is the credit risk of the borrower that matters here. As with many forms of consumer credit, the future cash flows (loan payments) associated with a student loan portfolio are highly uncertain in both timing and amount, and this payment uncertainty may well have a large component of so-called ‘market risk’. (This is a somewhat esoteric topic which should be familiar to students of finance familiar with the notion of ‘cost of capital’. But I will not go into it here.) And so while long-term lenders to the US Treasury in fiscal 2021 might reasonably have expected to earn an annual ‘risk free’ return of only 2% (short-term rates were then at or close to zero), the capital market clearing rate of return for a non-guaranteed student loan portfolio would have been much higher. Because the federal government is prohibited by law from selling or securitizing student loans from its portfolio, we do not have a market price to use in estimating the correct discount rate. But it would likely have been much higher than 2%.

OK, but is this matter of discount rates really such a big deal? In a word, yes. Let’s look at a couple of examples which demonstrate the impact of varying discount rate assumptions on the economic present value of a hypothetical loan portfolio. A single cash flow of $1 billion expected to be received 10 years from now has an economic present value (PV) of $820 million when discounted at an annual rate of 2% (the old UST bond yield) and $710 million when discounted at 3.5% (a more recent UST yield), but only $614 million when discounted at 5% (a hypothetical expected return estimate for a consumer loan portfolio). Similarly, a constant payment annuity with a 10-year life and cash flows of $1 billion a year (with zero growth and no terminal value) has a present value of about $9 billion if the cash flows are discounted at 2%, $8.3 billion if discounted at 3.5%, and $7.7 billion if discounted at 5%. And note that these are the values only if those $1 billion estimated cash flows accurately reflect the expected (probability adjusted) cash flows and have already been discounted to net off the amount of expected credit losses, a not unimportant caveat in the context of student loans.

I am not the first (nor will I be the last) person to have commented on this apparent disconnect between GAO accounting and how financial instruments are valued in the capital markets. The CBO (Congressional Budget Office) published a paper in March 2012 on Fair-Value Accounting for Federal Credit Programs, which discusses in great detail this issue of what discount rate to use for determining the ‘cost’ and ‘subsidy’ associated with federal credit programs, including the student loan program. In its 2012 paper, the CBO estimated that using a capital market discount rate instead of a government borrowing rate (as the GAO has done, consistent with the legal mandate of the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990), would increase the estimated federal subsidy associated with student loans issued between 2010 and 2020 from negative 9% to positive 12%, a negative swing (to the taxpayer) of 21 percentage points. Which of course is a very large difference. (Disclaimer: Many academics and policy makers do not agree that ‘fair value’ accounting should be applied to the student loan program. And while the CBO does not take a firm position on this issue, the arguments it makes in favor of FV accounting seem strong to me.)

And so we have good reason, I think, to question the economic integrity of the GAO’s estimate. If the GAO thinks the $1.6 trillion federal student loan portfolio is only worth $1.4 billion or so when the expected cash flows are discounted at 2% (reflecting an embedded $200 billion economic loss), then the estimated ‘fair value’ using a higher capital markets discount rate might well reduce the amount by another 20% or so, in line with the CBO’s 2012 FV-adjustment estimates. This would reduce the estimated market value of the federal student loan portfolio to less than $1.2 trillion, a 25% discount to the $1.6 trillion face value (ie the nominal amount owed). And this $400+ billion loss represents in effect an economic (if not accounting) subsidy from taxpayers to federal student loan borrowers, expressed in PV terms but payable (in cash) over time.

The Cost of Biden-Harris. As discussed in my prior post, the economic cost to the federal government of the Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan is not known with any degree of certainty. Initial cost estimates for just the loan cancellation portion of the plan ranged from $240 billion (initial Biden estimate) to $360 billion (CRFB) to $500 billion (Penn Wharton). Cost estimates for the proposed revisions to federal income-based repayment plans also varied widely, ranging from $120 billion (Biden) to $240 billion (CRFB) and as high as $500 billion (Penn Wharton). The cost of extending the covid payment moratorium through December 31 is estimated at another $15-20 billion.

On September 26, the CBO came out with its own initial estimate of the cost of just the loan cancellation portion of the Biden-Harris Plan. At $400 billion, the CBO estimate is about 67% higher than the initial Biden estimate and is pretty much right on top of the initial CRFB estimate. The CBO and Biden estimates vary due to different assumptions (forecasts) relating to the assumed loan cancellation participation rate among eligible borrowers, the size of the average loan balances to be cancelled and how much of this cancelled debt would have eventually been repaid (with interest) and over what period of time. Both cost estimates appear to use a 2% discount rate—in effect using the GAO/FCRA accounting methodology, not ‘mark to market’ or ‘fair value’ accounting. But in this case, using the lower discount rate would overstate the present value cost impact of reduced future revenues resulting from loan cancellation relative to cost estimates using a higher discount rate, relative to the fair value approach.

The CBO has not yet estimated the cost of the proposed revisions to the federal income-based repayment plan(s), which the Biden Administration initially estimated at $120 billion and the CRFB estimated at twice that. And while this portion of the Biden-Harris Plan has not gotten as much press or popular attention as the outright loan cancellation, and is more limited in scope than many commentators seem to think, it may well turn out to be a long-lasting and very consequential part of Biden-Harris.

And what about the distributional impact of Biden-Harris? In a recently issued report, the CBO estimates that over half of the financial benefits of the Biden-Harris debt cancellation plan—between 57% and 65%, including the impact of the 3-month payment moratorium—would accrue to those student loan debtors in the upper half of the income distribution. This should not surprise us, as college students (and therefore student loan borrowers) come disproportionately from families with household incomes above the national median and college graduates tend to earn a lot more money than non-graduates. The median annual income from all US households is roughly $60,000, but for households with some amount of education debt the median is higher at around $70,000 and for households headed by a college grad the median is closer to $100,000. So yeah, of course the financial benefits of an across the board student loan cancellation plan will accrue disproportionately to those with relatively higher incomes. (Just as a cut in the top marginal federal tax rate would disproportionately benefit those with higher than average incomes.)

But note that this purported ‘regressively’ occurs primarily because the CBO has measured the financial benefits of student loan cancellation not in terms of the absolute amount of debt cancelled—where the impact is almost exactly proportional (49% vs 51%)—but rather by the present value of the expected future payments associated with the to-be-cancelled debt. Student loan debtors from the top parts of the income distribution not only tend to owe relatively larger amounts of money (often because they attended graduate school), they also tend to pay back their debts in full and on time (thanks to their higher post-graduation incomes), increasing the PV of their to-be-cancelled future loan payments This makes sense from a financial perspective, but I suspect that this is not at all how most of the public, and many of our elected representatives, understand the analysis.

The Biden-Harris Plan counteracts some (or much) of this apparent regressively by removing from the loan cancellation program debtors with incomes in the top 5% of the distribution and by doubling the amount of loan cancellation for Pell grantees, who tend to come from the very low end of the US family income distribution. The Biden-Harris Plan is almost certainly ‘regressive’ in some important sense, but the amount of regressively looks very different if we measure impact by absolute amount of debt cancelled than by the present value of that debt or if we focus on the number of borrowers impacted rather than the amount of debt cancelled.

And for what is worth, the Biden-Harris Plan is pitched by its sponsors as a ‘middle-class’ debt relief plan. Which it certainly is, whether you like it or not.

Putting it all together. Putting all of this together suggests to me (using third party estimates and fair value accounting) thaet the federal government’s current $1.6 trillion (face value) student loan portfolio may have an economic present value as low as $1.2 trillion pre-Biden Harris, and perhaps $800 billion or less pro forma for Biden Harris. If this is correct, then the embedded loss (subsidy) associated with the federal student loan program constitutes 25-50% (or more) of the face value of the outstanding loans (pre and post-Biden Harris). And these are the expected losses (subsidies) embedded just in the current loan portfolio. They do not include any losses or subsidies associated with student loans issued in the future (either pre or post-Biden Harris).

When thinking about these numbers, however, a healthy degree of skepticism is warranted, a point emphasized by the CBO. As with all DCF valuations, the calculated present value of a stream of future cash flows depends critically on the accuracy of the underlying cash flow forecasts (including estimated loss on default) and also on the discount rate used, both of which are subject to estimation uncertainty and to changes over time. And while DCF valuations are expressed in present value terms, the corresponding cash flows (including losses from payment delinquencies, defaults and loan modifications or cancellation) occur only over time. My understanding is that the federal government will account for the full PV impact of Biden-Harris in the year of adoption, increasing that year’s fiscal deficit, but the cash flow and funding impacts will only be recognized over time.

But whatever the actual numbers, it seems clear that the US federal student loan program has over time evolved from what was originally intended to be a profitable (or at least break-even) financial proposition for the US taxpayer into a heavily subsidized program. This was almost certainly true by 2019, but the subsidy got much bigger during covid and will increase substantially if Biden-Harris is fully implemented. And at some point, heavily subsidized student loans begin to look a lot like grants, which is not at all what they were initially intended to be.

Which of courses begs the question: what does the US taxpayer get in exchange for all this subsidy?

The public policy rationale. Most government programs involve explicit or implicit subsidies of some amount, and so we should not be at all surprised to learn that the federal student loan program is in fact heavily subsidized. As perhaps it should be. But it is one thing to justify an annual subsidy of say 5% of the amount of newly issued loans and quite another to quadruple the subsidy with wholesale loan cancellations and modifications as proposed by Biden-Harris. At some point along this spectrum, the federal student loan program will have morphed from one of debt financing to one of publicly funded grants. And if this is the case, perhaps it would be best to acknowledge this up front.

In my last post I raised a few personal concerns about Biden-Harris, including the questionable legal basis for the loan cancellation by executive order; the perceived unfairness of the wholesale cancellation of student loan debt for current but not future (or past) debtors; and the moral hazard and adverse selection risks associated with loan cancellation and modification generally. But I also noted more favorably that the Biden-Harris Plan concentrates debt relief primarily on large numbers of low-income borrowers with relatively small individual debts who mostly attended community colleges and private for-profit programs (often not graduating), rather than on the much smaller number of debtors who borrowed much larger amounts of money (eg our Columbia MFA Film grads) and who collectively owe the bulk of the outstanding federal debt. I also noted that the real cost of granting loan relief structured this way may be much lower than one might think given the historically high delinquency and default rates among this cohort of borrowers. (If a loan is unlikely ever to be repaid, it doesn’t really cost much to forgive it.)

For two very thoughtful (but differing) perspectives on the merits of Biden-Harris, I encourage you to read here and here.

But whatever we may think about Biden-Harris, what exactly is the rationale for federal student aid and for student loans in particular?

There are no doubt many credible policy rationales for federal aid to higher education in some form and amount: for example to develop a more enlightened citizenry, to insure a globally competitive workforce, and/or to incentivize basic and applied research. But it seems to me that the strongest case for public funding (and subsidies) of direct student aid, particularly at the federal level, relates to the impact these programs may have on equality of opportunity in this country. If a ‘university’ education is in fact the ticket to ‘success’ in America—a premise that I think needs to be challenged more rigorously than it has been—then for reasons of social justice this opportunity should perhaps be made available equally to all.

But ‘equity’ is only one aspect of this debate, albeit an important one. We also need to talk about ‘efficiency’, and consider how well our taxpayer dollars are being spent (or invested) in today’s federal student aid programs. The economic cost (or subsidy) associated with the federal student loan program comes in large part from borrower payment delinquencies and defaults, which seem to be concentrated among two primary debtor cohorts: (i) the large number of often poor students who attend relatively low quality schools or programs and who don’t earn enough money after leaving school (with or without a degree) to repay their debts, even though the amounts they borrow individually tend to be small; and (ii) the smaller number of individuals who borrow much larger amounts of money to obtain undergraduate and graduate degrees of little apparent commercial value, and who also struggle to repay their much larger individual student loan debts.

Using admittedly extreme examples from the press, does it really make sense for the US taxpayer to finance 90% of the cost of attendance to students at community colleges and private for-profit universities with exceptionally low graduation and high default rates? How about $50,000 in loans to attend the undergraduate dance program at a notoriously high cost private nonprofit university? Or twice that that for a MFA film degree? Or three times that for a JD from a bottom tier law school? And to continue doing so year after year when the empirical evidence makes demonstrably clear to all concerned that a large portion of these students will make little if any more money after completing their degrees than those who chose not to get more education and went to work instead, rendering them unable to repay their debts? And lest we think that these are just extreme anecdotal examples (which they are), of little relevance to the public policy debate, keep in mind that something like 75% of students enrolled in private for-profit schools do not graduate, one-third of all student loan debtors leave school with debt but no degree, and that borrower default rates run at around 25% for students attending community college and 50% for those at private for-profits. Somehow this doesn’t seem quite right.

And let’s not forget that the primary reason most students want to invest in higher education is because the private financial benefits are expected (not guaranteed) to justify the investment, and generally do so (at least on average). And the reason a rational lender is willing to finance the investment is because there is a high likelihood of borrower repayment, with expected loss on default compensated by the credit spread (interest rate) on the loan. (Perhaps with a bit of subsidy from governmental lenders.) But why should the government fund the vast majority of these private investments, instead of leaving the job primarily or exclusively to the private sector?

The answer of course is because of the pervasive disparity in family wealth and financial capacity in this country and the clear credit impediments to private market funding of 18+ year-olds with few financial resources and no collateral to borrow against. Of course there does exist today a small private student loan market, which might be larger in the absence of subsidized federal funding, but we know from past experience with the FFELP and Perkins loans that this market only really worked when the federal government (or parents) agreed to guarantee all of the credit risk. (We also do this with residential mortgage financing, using Fannie & Freddie, but in that case the borrowers are adults with jobs and credit histories, down payments and houses to use as collateral.)

On balance I think one can make a strong public policy case to expand our current programs of direct federal student aid targeted to particularly needy segments of our population supported by a large (but perhaps restructured) federal student loan program. But in doing so I think we also have to find a way to enhance the outcomes for many student borrowers, particularly those facing the biggest challenges to successful completion of worthwhile educational programs. We can’t guarantee individual student outcomes, of course, but we probably can improve the odds.

In conclusion. I don’t know how things will play out with Biden-Harris and I don’t have well-informed views on what our federal student aid and student loan programs should look like going forward. But it seems to me and to many others that what we are doing now is not working as well as it should, at least in certain segements of our higher education system. And while the root causes of this failure likely do not lie entirely or even primarily with federal funding—our schools, students and parents have to shoulder some of the blame too—it does seem to me that the now heavily subsidized federal student loan programs may have contributed in significant ways to large amounts of uneconomic educational investment over many years. This needs to change, and the Biden-Harris proposal to cancel currently outstanding student debts addresses merely the symptoms and not the root causes of this particular problem. In fact it may make the problem worse if borrowers increasingly view student loans (with overly generous income-based repayment plans) as ‘free money’.

Let me close on a more upbeat note however and refer you all to a wonderful West Wing episode in which one of the characters explains to Toby and Josh in an Indiana hotel bar how paying for his daughter’s college education should be a challenge but it should not be impossible. And that even just a bit more federal financial support could make all the difference to millions of hard-working Americans trying to help their kids get a good start in life.

These are noble sentiments which I think most of us probably share, and no doubt this is what the Biden Administration is in good faith attempting to do with some of its proposals. But I think we all need to be wary of unintended consequences, particularly the very real risks of ‘moral hazard’ and ‘adverse selection’ on future borrower behavior. As they say, the devil is in the details and I am not sure that Biden-Harris has gotten the details entirely right, perhaps far from it.

As they also say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. And in the case of Washington DC, with billions of dollars of taxpayer subsidy as well.

Links:

Understanding Federal Student Aid. Department of Education.

Federal Student Loans: What are they and how to apply, SLMAE

The Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan, DOE press release, August 24, 2022

The Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan, White House Fact Sheet, August 24,2022

Banking & Beyond: The Biden-Harris Student Debt Relief Plan, September 11, 2022

Is the US Student Loan Program Profitable? Washington Post, July 2013

GAO Student Loan Report, July 2022

Fair-Value Accounting for Federal Credit Programs, CBO, March 2012

CBO Estimate of the Cost of Biden-Harris, September 26, 2022

DOE Student Aid Overview, Fiscal 2021 Budget Request

Why I Changed My Mind on Student Debt Relief, NY Times August 2022

Biden’s Student Loan Plan has Issues, NY Times Op-Ed, September 27, 2022

Is Biden’s Student Debt Plan Still Regressive? CRFB Report, 3 October 2022