Subsidizing Student Loans

How much and why?

This is my fifth post on various aspects of our national student loan ‘problem’. My last post, on the Biden-Harris Student Debt Relief Plan, examined the changing demographics of student loan borrowers, speculated as to who might benefit the most from the Biden-Harris Plan, and offered up a few preliminary observations about the policy merits of the Plan itself. In today’s post, I will probe more deeply into the economics of the federal student loan program, focusing on its profitability and the size of the federal subsidy embedded in the government’s current loan portfolio, and conclude by probing the public policy rationale for the federal student loan program.

Setting the stage. For the most recent fiscal year (which ends September 30th), the US government granted students and their parents approximately $125 billion of direct financial support to pay for higher education expenses, consisting of $30 billion in grants (almost entirely Pell grants) and another $95 billion in federal student loans. The loans were issued to students (and the parents of students) who attended vocational training programs and community colleges, public and private undergraduate universities, and various graduate and professional degree programs. The loans were offered through several federal student loan programs, in varying loan amounts and mostly without credit checks or third-party guarantees. The interest rates on recently issued federal student loans range from 5% to 7.5% (plus fees), with interest accrual and repayment terms varying by the type of loan.

The US government’s current student loan portfolio has a face value (nominal amount) of around $1.6 trillion (as of June 30, 2022) and comprises the unpaid balance owed on loans going back at least 25 years, to 1997. (A surprising number of borrowers still owe student loan debt well into their retirement years.). Another $150 billion or so of outstanding student loan debt was issued pursuant to private student loan programs, which are generally more expensive than federal loans and often require credit checks and/or third-party (often parental) guarantees. The outstanding federal loans will for the life of the loans remain on the balance sheet of the US government, which is prohibited by law from selling or securitizing them (unlike lenders in the private market). (Note: There is an active secondary market in securitized student loans (Student Loan Asset Backed Securities, or SLABS), which consists primarily of privately issued student loans guaranteed by the federal government under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP), which was discontinued back in 2010.)

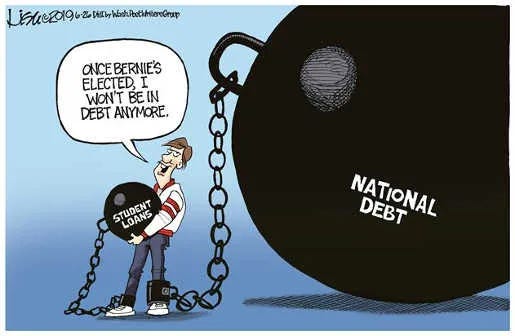

Politicians, educators and others have for years debated the structure and public policy merits of the US federal student loan program, a debate which has grown in intensity with the announcement a month ago of the Biden-Harris Student Debt Relief Plan. The Biden-Harris Plan proposes to cancel outright 20-25% or so of the total outstanding federal student loan debt and to reduce significantly the future repayment burden on qualifying borrowers participating in federal income-based repayment plans. (I wrote about Biden-Harris in my last post, which you can read here.)

And so perhaps now is a good time for us to dig a bit deeper into the economics of the federal student loan program, focusing on the profitability of the program and the amount of taxpayer subsidy embedded in the current loan portfolio, which may shed some light on the current public policy debate triggered by Biden-Harris Plan.

Was the US federal student loan program profitable before Covid and Biden-Harris? Back in 2013, Senator Elizabeth Warren described as ‘obscene’ the profitability of the US federal student loan program. That year, the Department of Education (DOE) reported that the US federal student loan program had generated an annual profit of $50 billion on a loan portfolio with a face value of around $1 trillion. This represented a 5% or so pre-tax return on assets, which may or may not have been ‘obscene’ but was certainly healthy compared to the profitability of the consumer banking industry, which at the time probably generated an aggregate NIM (net interest margin = net interest income/interest earning assets) of around 3% and a pre-tax profit margin (including non-interest revenues and expenses) below 2%.

But that was back in 2013, and we have good reason to believe that the profitability of the federal student loan program has declined markedly since then, and particularly in the last several years.

The GAO Report. In July 2022, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) issued its revised calculation of the expected profitability of the federal government’s outstanding student loan program. The GAO reduced its previous estimate of a $100 billion profit (‘negative subsidy’ in government accounting terminology) to a $200 billion loss (‘positive subsidy’). Almost 40% of this $300 billion revision was attributable to the covid-related payment moratorium initiated under the Trump Administration and continued (and extended) under Biden. The balance came from revised downward estimates of future revenues from student loan payments, attributable to a number of factors including higher than expected credit losses and an increased number of borrowers participating in income-based repayment plans. And all of this was before any anticipated impact from the Biden-Harris Plan.

The GAO’s analysis was conducted in line with conventional (and legally mandated) government accounting standards, but there is reason to believe that the GAO may actually have understated the size of the economic loss (subsidy) embedded in the federal student loan portfolio. Using its own present value methodology, the GAO discounted its revised estimates of future cash flows (borrower payments) to present value at a discount rate equal to the government borrowing rate, at the time 2%. But while 2% may have been the right rate to use in measuring the government’s actual cost of funding (eg for calculating NIM), it does not seem like an appropriate rate to use for calculating the economic present value of a risky student loan portfolio.

To restate the obvious, in the federal student loan program the US government is the lender not the borrower, and it is the credit risk of the borrower that matters here. As with many forms of consumer credit, the future cash flows (loan payments) associated with a student loan portfolio are highly uncertain in both timing and amount, in a word ‘risky’. And so while long-term lenders to the US Treasury in fiscal 2021 might reasonably have expected to earn an annual return of only 2% (short-term rates were then at or close to zero), the capital market clearing rate for a non-guaranteed student loan portfolio would have been much higher, perhaps on the order of 5% or so. Because the federal government is prohibited by law from selling or securitizing student loans from its portfolio, we do not have a market price to use in estimating the correct discount rate. But it sure was not 2%.

OK, but is this matter of discount rates really such a big deal? In a word, yes. Let’s look at a couple of examples which demonstrate the impact of varying discount rate assumptions on the economic present value of a hypothetical loan portfolio. A single cash flow of $1 billion expected to be received 10 years from now has an economic present value (PV) of $820 million when discounted at an annual rate of 2% (the old UST bond yield) and $710 million when discounted at 3.5% (a more recent UST yield), but only $614 million when discounted at 5% (a hypothetical expected return estimate for a consumer loan portfolio). Similarly, a constant payment annuity with a 10-year life and cash flows of $1 billion a year (with zero growth and no terminal value) has a present value of about $9 billion if the cash flows are discounted at 2%, $8.3 billion if discounted at 3.5%, and $7.7 billion if discounted at 5%. And note that these are the values only if those $1 billion estimated cash flows are the expected (not nominal scheduled) cash flows and have already been discounted to net off the amount of expected credit losses, a not unimportant caveat in the context of student loans.

And so we have good reason, I think, to question the economic integrity of the GAO’s estimate. If the GAO thinks the $1.6 trillion federal student loan portfolio is only worth $1.4 billion or so when the expected cash flows are discounted at 2%, then the real value of the portfolio will be much lower when discounted at a market clearing rate of say 5%. I don’t have the data to do the analysis, but I would not be surprised if the real economic present value of the federal student loan portfolio was as low as $1.2 trillion, a 25% discount to the $1.6 trillion face value (ie the nominal amount owed). And this $400 billion loss represents in effect a subsidy (over time) from taxpayers to federal student loan borrowers.

The Cost of Biden-Harris. As discussed in my prior post, the cost to the federal government of the Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan is not known with any degree of certainty. Initial cost estimates for just the loan cancellation portion of the plan ranged from $240 billion (initial Biden estimate) to $360 billion (CRFB) to $500 billion (Penn Wharton). Cost estimates for the proposed revisions to federal income based repayment plans also varied widely, ranging from $120 billion (Biden) to as high as $500 billion (Penn Wharton). The cost of extending the covid payment moratorium through December 31 is estimated to cost another $15-20 billion, just a drop in the overall Biden-Harris bucket.

Just a few days ago, the CBO came out with its own initial estimate of the cost of just the loan cancellation portion of the Biden-Harris Plan. At $400 billion, the CBO estimate is about 67% higher than the initial Biden estimate and is pretty much right on top of the initial CRFB estimate. The CBO and Biden estimates vary due to different assumptions (forecasts) relating to the assumed participation rate among eligible borrowers, the size of the average loan balances to be cancelled and how much of this cancelled debt would have eventually been repaid (with interest) and over what period of time. Both cost estimates appear to use a 2% discount rate, which in this case would overstate the present value cost impact of reduced future revenues resulting from loan cancellation relative to cost estimates using a higher rate.

The CBO has not yet estimated the cost of the proposed revisions to the federal income-based repayment plan(s). And while this portion of the Biden-Harris Plan has not gotten as much press or popular attention as the outright loan cancellation, and is more limited in scope than many commentators seem to think, it may well turn out to be a long-lasting and consequential part of Biden-Harris.

Putting it all together. Putting all of this together suggests to me (using third party estimates) that the federal government’s current $1.6 trillion (face value) student loan portfolio may have an economic present value as low as $1.2 trillion pre-Biden Harris, and perhaps $800 billion pro forma for Biden Harris. If this is correct, then the embedded loss (subsidy) associated with the federal student loan program constitutes 25-50% of the face value of the outstanding loans (pre and post-Biden Harris). And these are the expected losses (subsidies) embedded just in the current loan portfolio. They do not include any losses or subsidies associated with future student loan grants (either pre or post-Biden Harris).

When thinking about these numbers, however, a healthy degree of skepticism is warranted, a point emphasized by the CBO. As with all DCF valuations, the calculated present value of a stream of future cash flows depends critically on the accuracy of the underlying cash flow forecasts and also on the discount rate used, both of which are subject to estimation uncertainty and to changes over time. And while DCF valuations are expressed in present value terms, the corresponding cash flows (including losses from payment delinquencies, defaults and loan modifications or cancellation) occur only over time. My understanding is that the federal government will account for the full PV impact of Biden-Harris in the year of adoption, but the cash flow and fiscal (funding) impacts will only be recognized over time.

But whatever the actual numbers, it seems clear that the US federal student loan program has over time evolved from what was originally intended to be a profitable (or at least break-even) financial proposition for the US taxpayer into a heavily subsidized program. This was almost certainly true by 2019, but the subsidy got much bigger during covid and will increase substantially if Biden-Harris is fully implemented.

Which of courses begs the question: what does the US taxpayer get in exchange for all this subsidy?

The public policy rationale. Most government programs involve explicit or implicit subsidies of some amount, and so we should not be at all surprised to learn that the federal student loan program is in fact heavily subsidized. As perhaps it should be. But it is one thing to justify an annual subsidy of say 5-10% of the amount of newly issued loans and quite another to double or triple the subsidy with wholesale loan cancellations as proposed by Biden-Harris.

In my last post I raised a few personal concerns about Biden-Harris, including the questionable legal basis for the loan cancellation by executive order; the perceived unfairness of the wholesale cancellation of student loan debt for only the current cohort of debtors; and the moral hazard risk associated with loan cancellation generally and the substantial expansion and relaxation of federal income-based repayment plans in particular. But I also noted in support that the Biden-Harris Plan concentrates debt relief primarily on low-income borrowers, many of whom seem to have been ill-served by our higher education system (eg those attending private for-profit schools). I also noted that the real cost of granting loan relief to low-income debtors may be less than one might think given the historically high delinquency and default rates among this cohort of borrowers. (If a loan is unlikely ever to be repaid, it doesn’t really cost much to forgive it.)

For two very thoughtful (but differing) perspectives on the merits of Biden-Harris, I encourage you to read here and here.

But whatever we may think about Biden-Harris, what exactly is the rationale for federal student aid and for student loans in particular?

There are no doubt many credible policy rationales for federal aid to higher education in some form and amount: for example to develop a more enlightened citizenry, to insure a globally competitive workforce, and/or to incentivize basic and applied research. But it seems to me that the strongest case for public funding (and subsidies) of direct student aid, particularly at the federal level, relates to the impact these programs may have on equality of opportunity in this country. If a ‘university’ education is in fact the ticket to ‘success’ in America—a premise that I think needs to be challenged more rigorously than it has been—then for reasons of social justice this opportunity should perhaps be made available equally to all.

But ‘equity’ is only one aspect of this debate, albeit an important one. We also need to talk about ‘efficiency’, and consider how well our taxpayer dollars are being spent (or invested) in today’s federal student aid programs. The economic cost (or subsidy) associated with the federal student loan program comes in large part from borrower payment delinquencies and defaults, which seem to be concentrated among two primary debtor cohorts: (i) the large number of often poor students who attend schools or programs of questionable value and who don’t earn enough money after leaving school (with or without a degree) to repay their debts, even though the amounts they borrow individually tend to be small; and (ii) the smaller number of individuals who borrow much larger amounts of money to obtain undergraduate and graduate degrees of little commercial value, and who also struggle to repay their much larger individual student loan debts.

Using admittedly extreme examples from the press, does it really make sense for the US taxpayer to pay 90% or more of the cost for students to attend dodgy private for-profit programs in say cosmetology? How about $100,000 in loans to attend the undergraduate dance program at USC? Or twice that for a Columbia MFA film degree? And to continue doing so year after year when the empirical evidence makes demonstrably clear to all concerned that a large portion of these students will make little if any more money after completing their degrees than those who chose not to get more education and went to work instead? And lest we think that these are just extreme anecdotal examples (which they are), of little relevance to the public policy debate, keep in mind that something like 75% of students enrolled in private for-profit schools do not graduate, one-third of all current student loan debtors left school with debt but no degree, and that default rates among community college student borrowers run at around 25% and 50% at private for-profits.

No, of course not. I don’t think you have to be a Tea Party conservative to believe that this sort of subsidized federal funding does not make sense, at least not from an ‘efficiency’ or ‘effectiveness’ point of view. And from the perspective of the US taxpayer, the situation today would likely be even worse if we had given these students grants instead of student loans. The student outcomes might not have changed much, but at least with a loan there is some chance of the taxpayer getting a partial repayment, however small.

And let’s not forget that the primary reason most students want to invest in higher education is because the private financial benefits are perceived to justify the investment, and generally do so (at least on average). But why should the government fund these private investments, instead of leaving the job entirely to the private sector?

The answer of course is because of the pervasive disparity in family wealth and financial capacity in this country and the clear impediments to private market funding of 18 year-olds with no access to family wealth, no credit history and no collateral to borrow against. Of course there does exist today a small private student loan market, which might be larger in the absence of subsidized federal funding, but we know from past experience with the FFELP that this market only really worked when the federal government agreed to guarantee all of the credit risk. (We also do this with residential mortgage financing of course, using Fannie & Freddie, but in that case the borrowers are adults with jobs and credit histories, down payments and houses to use as collateral.)

And so I think we can make a clear and compelling public policy case to continue providing some amount of direct federal student aid targeted to particularly needy segments of our population. But in doing so I think we also have to find a way to insure that the money is being well spent, or at least better than seems to be the case today. We can’t guarantee individual student outcomes, of course, but we probably can improve the odds.

In conclusion. I don’t know how things will play out with Biden-Harris and I don’t have well-informed views on what our federal student aid and student loan programs should look like going forward. But it seems to me, and to many others, that what we are doing now is simply not working well too much of the time. And while the root causes of this failure may not lie entirely with federal funding of higher education—our schools and students (and parents) have to shoulder much of the blame too—it does seem to me that subsidized federal student aid (particularly through student loans) has been a great enabler of large amounts of uneconomic educational investment over many years. This needs to change, and the Biden-Harris proposal to simply write off bad debts will not solve this particular problem. In fact it may make the problem worse if borrowers increasingly view student loans as ‘free money’.

Let me close on a more upbeat note however and refer you all to a wonderful West Wing episode in which one of the characters explains to Toby and Josh in an Indiana hotel bar how paying for his daughter’s college education should be a challenge but it should not be impossible. And that even just a bit more federal financial support could make all the difference to millions of hard-working Americans trying to help their kids get a good start in life.

These are noble sentiments which I think most of us probably share, and no doubt this is what the Biden Administration is in good faith attempting to do with some of its proposals. But I think we need to be wary of unintended consequences, particularly the very real risk of ‘moral hazard’ on future borrower behavior. As they say, the devil is in the details and I am not sure that Biden-Harris has gotten this entirely right.

As they also say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. And in the case of Washington DC, with billions of dollars of taxpayer subsidy along the way.

Links:

Understanding Federal Student Aid. Department of Education.

Federal Student Loans: What are they and how to apply, SLMAE

The Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan, DOE press release, August 24, 2022

The Biden-Harris Student Loan Debt Relief Plan, White House Fact Sheet, August 24,2022

Banking & Beyond: The Biden-Harris Student Debt Relief Plan, September 11, 2022

Is the US Student Loan Program Profitable? Washington Post, July 2013

GAO Student Loan Report, July 2022

CBO Estimate of the Cost of Biden-Harris, September 26, 2022

DOE Student Aid Overview, Fiscal 2021 Budget Request

Why I Changed My Mind on Student Debt Relief, NY Times August 2022

Biden’s Student Loan Plan has Issues, NY Times Op-Ed, September 27, 2022