Inflation Post-Script

May inflation, stock prices, QE and Bernanke's new book

My last B&B Inflation post from earlier this week is already out of date. On Friday, May CPI came in higher than expected, the national average price of gas hit $5 a gallon, and the stock and bond markets tanked in response. And to make matters worse, the Celtics lost that night by 10 to even the series at 2-2. I have no idea what is coming next on the inflation front, but the odds of the Celtics winning the series, though reduced, are still better than the odds of making money in the stock market this year.

So what should we make of this week’s financial news?

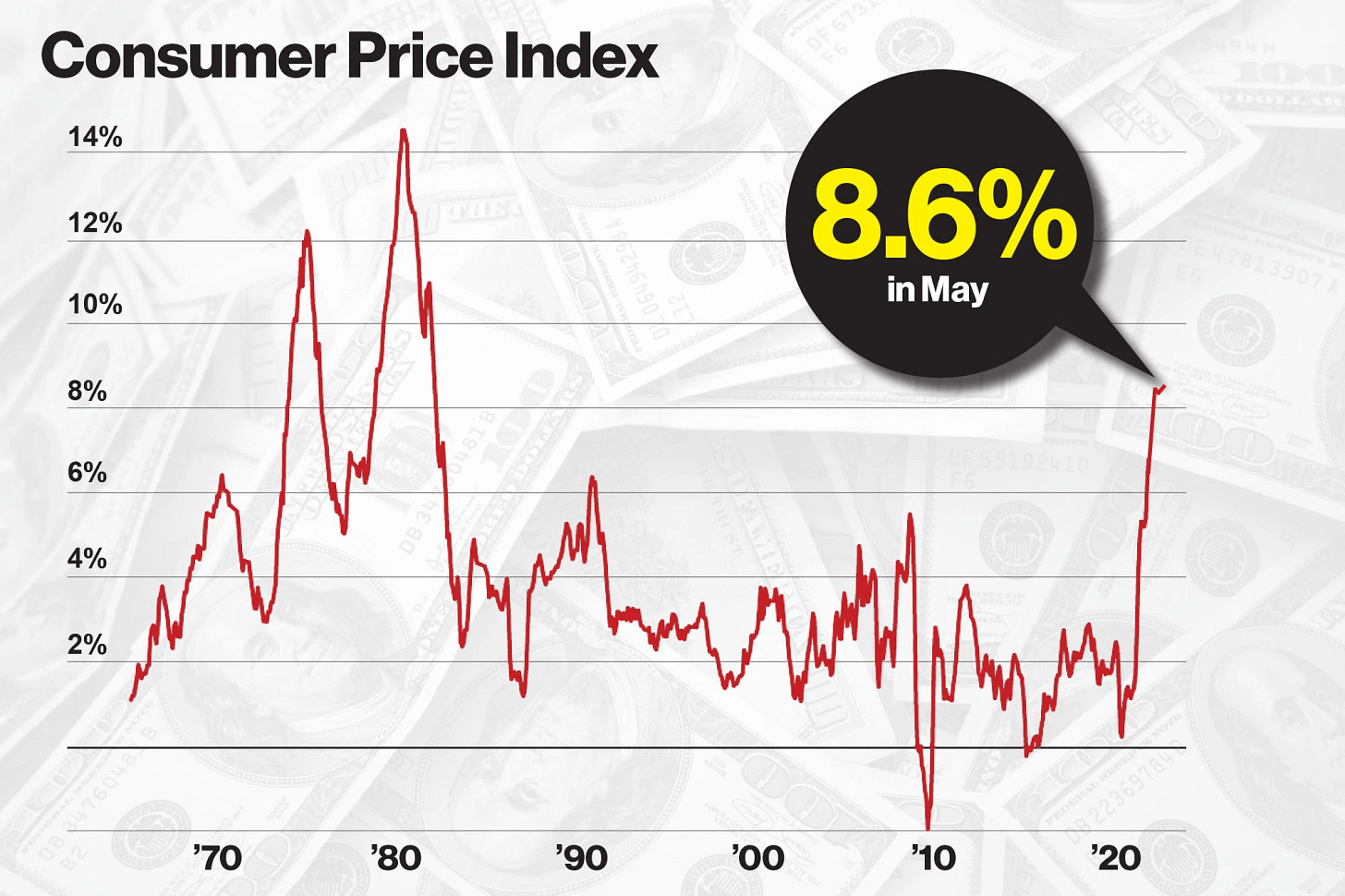

May CPI. Ouch! We all wanted to see better news, with at least some data confirming recent speculation (wishful thinking perhaps) that inflation might have passed its peak. (Recall that inflation is the rate of change in prices, not the level of prices, and so the level of prices will continue to go up even with a declining rate of inflation.) But this was not to be. May’s CPI was up 1% month on month (seasonally adjusted) and 8.6% year on year. The May increase was broad-based, with the indexes for shelter (+5.5%), gasoline (+48.7%), and food (+10%) being the largest contributors. (Not all of these factors are equally weighted in the index.)

Excluding the volatile food and energy components, CPI still rose 0.6 percent in May (seasonally adjusted) and 6.0% year on year. The index for airline fares continued to rise, increasing 12.6 percent in May after rising 18.6 percent the prior month, confirming what you will already have discovered if you booked any air travel recently. And reversing recent trends, the index for used cars and trucks rose 1.8 percent in May after declining in each of the 3 prior months. The index for new vehicles rose in May, increasing 1.0 percent after rising 1.1 percent in April.

All in all, this was a gloomy report which was not well received in Washington, on Wall Street or on Main Street.

The capital markets response. Double ouch!! The stock market and the bond market both traded down significantly on the inflation report, with renewed speculation that the Fed may be forced to raise rates more aggressively in the coming months and with growing fears of a near-term recession and a further fall in corporate profits. The broad US stock market was down ca 3% on Friday, a bit less for the Dow and a bit more for the Nasdaq. Overall the S&P 500 was down 6% for the week and it is now down 19% year to date. For QQQ (the Nasdaq 100 index), the numbers for the same periods are down 7% and down 28% respectively. Bitcoin was down 10% for the week and is now off 40% YTD. (So much for crypto as a store of value in high inflation periods.)

Bond prices also fell and the yield on the ten-year UST now stands at 3.15%, up about 20bps on the week and having essentially doubled since the beginning of the year (from 1.6%). The yield on US TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) has increased by 150bps, from negative 1.1% at the beginning of the year to positive 0.4% now, offering investors at long last a modest positive real yield (before taxes). Corporate bond spreads have widened by 50 bp over the past year, but are still relatively tight, reflecting perceived low (but rising) default risk. And the forex value of the US dollar (DXY) has continued to climb in line with increasing interest rate differentials, up 2% on the week and up 17% on the year.

Suffice it to say we are now firmly in a “risk off” market, and approaching a technical bear market (down 20%) in US equities, which is quite a change from most of the last 10+ years. Unfortunately, there may well be more carnage to come before things begin to improve.

Investment strategy. For some time now, the chief driver of much investment strategy has been TINA: There Is No Alternative (to stocks). With short-term interest rates at or below zero, longer-term bond yields also very low, and tight credit spreads, there really was no good alternative to stocks. And so everyone piled into equities, including retirees with relatively short investment time horizons. With UST yields now rising above 3%, twice the dividend yield on US stocks, perhaps investors (particularly retirees) will again consider adding some bonds back into the mix. However with US inflation now heading toward 10%, and the Fed rapidly raising rates, this may not yet be the time to do so. Inflation is horrible for fixed income investments (eg bonds), as are rising interest rates, and stocks have historically offered at least some (limited) protection against inflation. But of course equity valuations are also sensitive to the level of interest rates and equities are more vulnerable to recession risks than are UST bonds. All of which leaves many investors scratching their heads, reducing their exposure to both equities and corporate credit (eg high yield bonds and leveraged loans) and increasing their allocations to cash, at least temporarily. Cash does not earn much today (1%), but at least it will hold its value in nominal (if not real) terms while we wait to see how things play out.

For those of you interested in investment management or private wealth management, I encourage you to read the James Mackintosh piece in yesterday’s WSJ, Abandon Stocks for Bonds?

Reconsidering QE. The recent increase in inflation has refocused attention on the Fed’s unorthodox program of quantitative easing (QE), which increased the size of the Fed balance sheet by $8 trillion (up 9x) since late 2008. (About $3.5 trillion of the increase came in response to the 2008 financial crisis and the balance came in response to the covid pandemic in 2020, with a few modest reductions in between.) The goal of QE was to lower long-term interest rates and thereby stimulate business and consumer investment in a prolonged weak economy with minimal room to further reduce short-term rates (which were already at zero). And the vehicle for doing this was Fed purchases of longer-term bonds, almost exclusively UST and GSE mortgage bonds, paid for with newly created bank reserves (deposits at the Fed), commonly (if not quite correctly) referred to as “printing money”.

QE largely worked as it was intended, driving a big drop in long-term interest rates, with 10-year UST yields falling from 5% before the financial crisis to a low of 0.5% during covid. QE and the resulting increase in bond prices (fall in bond yields) also incentivized investors to increase their exposure to risk assets, resulting in a large increase in the price (valuation) of stocks, junk bonds and crypto, as well as housing (more recently). The market value of US stocks (S&P 500) increased by over 6x from its 2009 low to its peak in December 2021 and the average price of US houses (Case-Shiller index) doubled from 2012 to 2022. The increased price of financial assets resulting from QE had significant allocative distortions, as became increasingly clear over time, but these were viewed by (most) policymakers as a necessary evil in order to achieve the broader goal of further stimulating the real economy (and particularly reducing unemployment). There was also some hope that QE might help stimulate the real economy more directly via the wealth effect. The conventional wisdom is that QE drove a substantial increase in wealth inequality in this country, reflecting the unequal distribution of individual share ownership, but the data is more mixed than one might expect.

Despite QE’s distortive impact on the price of financial assets, however, there was until recently little or no empirical evidence of rising inflation in the real economy (eg in consumer or producer prices). But there is today. Some vocal opponents of QE will remind us that they predicted this years ago—”printing money always causes inflation”— but these folks were wrong for well over a decade. Perhaps they were just early in their inflation call, but when it comes to financial policy and investment strategy there is not much difference between being early and being wrong, as students may recall from this classic clip from the film The Big Short.

QE remains highly controversial, but it is a much more complex and nuanced subject than you would understand just from reading the popular press (or even much of the financial press for that matter). We will no doubt hear more about this in the coming months and so it is worth spending some time understanding both the popular critique as well as the more nuanced economic analysis. For a short-version of the anti-QE thesis, you might read Christopher Leonard’s guest essay in yesterday’s NY Times, If You Must Point Fingers, Here’s Where to Point. And for a more nuanced analysis, I would refer you to Ben Bernanke’s new book (discussed below).

Bernanke’s new book. Ben Bernanke’s new book, 21st Century Monetary Policy, was published in May and I just finished reading it. This book is not what I would call a great summer read—it is after all a book on the history of monetary policy written by an academic economist. Nevertheless I can recommend this book without hesitation, particularly for those of you who last studied this subject back in the 1970s, as I did. (For more recent students, this is a good followup to the Bernanke book we read in our Financial Services class, The Fed and The Financial Crisis.) For those who aren’t likely to read the book, here is a review from the Washington Post.

A lot has changed in the world of central bank monetary policy over the past 50 years, and in this book Dr. Bernanke will walk you through it in excruciating (I mean great) detail. You won’t find any particular insights into the Fed’s current thinking, however, which will disappoint many readers (including me), but which no doubt reflects Dr Bernanke’s respect for central banking tradition. Retired Fed chairs generally do not criticize their successors, at least not without a substantial time lag, and neither does Dr. Bernanke, at least not on the record. (Oh that all our former presidents would follow this tradition.) After reading this book, you will have learned much about the intricacies and mechanics of monetary policy, perhaps more than you wanted to know, and you will also understand better how we got to where we are today.

Judging the Fed’s performance. As Bernanke’s book documents, the Fed has spent much of the past 14 years working with its counterparts at the US Treasury (and at other central banks) in an attempt to fend off what were perceived at the time as cataclysmic threats to the global financial system and the global economy, first in 2008 (the financial crisis) and then again in 2020 (the covid pandemic). This was done with a policy mix of unprecedented monetary accommodation, liquidity support and fiscal stimulus. In doing so, the Fed had to deal with the practical challenges of stimulating the economy in a world with zero interest rates, which rendered ineffective the traditional monetary policy tool of cutting short-term policy rates (fed funds). The Fed also had to deal at times with strong political resistance not only to its own unorthodox monetary policies but also to the more direct and powerful tool of fiscal stimulus. And it had to do so in a world of rapidly changing, and largely unprecedented circumstances, where the right way forward was never clear.

The Fed has a dual monetary policy mandate, to promote not only stable prices but also full employment, and it was the later goal which (rightly) took precedence for much of the period 2008-2021. And while the Fed is now being heavily criticized for the recent increase in inflation—and perhaps fairly so—we should not lose sight of its (shared) accomplishments in restoring full employment to the US economy. In part due to the Fed’s policies, the US unemployment rate has fallen to a record-low of 3.6%, down from almost 15% in 2020 (and 10% in 2010) and there are now 5 million more job postings than there are people seeking work. Our biggest labor problem today is not unemployment but worker shortages, which is quite a change from the recent past.

This does not mean that the Fed has done everything right, however. It has not, as the latest inflation numbers and the falling stock market make clear. And Fed Chair Powell has acknowledged as much. As I have said before, inflation is a real problem for real people and we should not underplay the importance of addressing our current inflation challenges, even while we acknowledge the importance of the Fed’s accomplishments on the employment front.

No, inflation is not a good problem to have, of course. But as is often said about growing old, it sure beats the alternative.

Links:

May CPI Report, BLS, 10 June 2022

US CPI Hits 8.6% in May. WSJ, 10 June 2022

Persistent Inflation Drags on US Stocks, WSJ, 10 June 2022

How High is Inflation and What Causes It? WSJ 10 June 2022

New Data Suggests Consumers Losing Confidence, WSJ 10 June 2022

Abandon Stocks for Bonds? WSJ, 11 June 2022

If You Must Point Fingers on Inflation, Here’s Where to Point Them, NY Times, 11 June 2022

Corporate Earnings Under Threat, WSJ 12 June 2022

Former Fed Chair Still Wants the Punch Bowl—And a High-Proof Punch, Washington Post, 27 May 2022