For the topic of today’s post, I want to give a shout out to former W&M student Abe Haji, who, after reading and commenting on my post Understanding the Fed: Book Recommendations, suggested that I read William Greider’s 1987 book on Paul Volcker’s Fed, Secrets of the Temple. The book is quite long, at over 700 pages, but I thought it was excellent and I recommend it to all of you who are seriously interested in the topic of central banking.

Given our current economic situation, with Jay Powell’s Fed attempting to quell a nasty bout of price inflation without throwing the US economy into recession, it is perhaps timely to reflect on the legacy of Paul Volcker, Fed chair from 1979-1987. Volcker was the last Fed chair before Powell to have battled significant inflation in the US economy and it has now been 35 years since he left office. During this time, the US economy experienced two decades of relatively stable economic conditions, followed by two major financial and economic crises, but very little in the way of serious price inflation until quite recently, which many people attribute to the legacy of Volcker’s time at the Fed. This may or may not be a sound reading of financial history, but I think it is fair to say that Paul Volcker left quite a legacy in the world of central banking and even today he still casts a very long shadow over Fed monetary policy.

But what exactly is the Volcker legacy, and what can we learn from it?

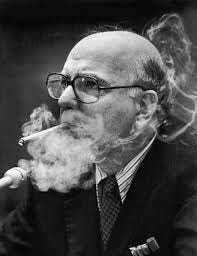

The Volcker Legacy. Paul Volcker is today widely regarded, respected and even revered as the giant of a man (he stood 6’7” tall) who in the early 1980s almost single handedly slayed the nasty dragon of US price inflation, which had developed over the prior two decades and which I have written about in prior posts. And there is much truth to this narrative. Volcker did sometimes seem to stand alone in the brutal war against inflation and his aggressive policy actions as Fed chair did succeed in squeezing inflation and inflationary expectations out of the US economy for a period of almost 40 years. But the full story of what happened during Volcker’s time as Fed chair is more complicated and in many respects less flattering to his legacy than is the “inflation slayer” myth as we remember it today.

William Greider’s 1987 book, The Secrets of the Temple, tells the story of Volcker’s time at the Fed and does so at great length (700+ pages) and in great detail but with a compelling and fast paced narrative that I found hard to put down. Importantly, Greider’s book addresses not only Volcker’s successes at the Fed but also his failures, which sometimes seem to get lost in contemporary evocations of the Volcker myth. I think Greider would agree with me when I say that Paul Volcker deserves to be remembered for his decisive victory in the war against inflation—this truly was an historic period in US financial history—as well as for his many other accomplishments in a long and dedicated career of exemplary public service. But we don’t do ourselves any favors by choosing to remember only the glory of past battles won and ignoring the substantial damage inflicted on those who fell along the way. Yes Volcker’s Fed did defeat inflation, and the victory was decisive, but this battle was won only at great cost to many of our citizens and to our social fabric.

Interest Rates and Unemployment under Volcker. To break the back of inflation, Volcker’s Fed took nominal interest rates above 20% and held real (inflation adjusted) interest rates at punitive levels of 8-10% well after reported inflation rates had reverted to low single digits. And Volcker pursued his aggressively tight monetary policy with few if any concessions to address the extensive collateral damage being inflicted on the real economy. Volcker’s policy actions as Fed chair threw the US economy into severe recession, drove the unemployment rate above 10% and effectively shut down several key sectors of the US economy, including the interest rate sensitive housing and construction industries. This was all viewed at the time as a painful but necessary part of Volcker’s war on inflation and had surprisingly broad support among the leadership of both political parties, despite substantial and growing public disenchantment. But the economic damage from Volcker’s policies went well beyond the immediate impact on employment—an intended and necessary part of Volcker’s anti-inflation plan—and changed the US and global economies in ways that still resonate today.

Collateral Damage. In addition to causing record levels of unemployment, Volcker’s monetary policies also inflicted substantial collateral damage on the US and global economy. Volcker’s high interest rate policies drove up the value of the US dollar and in the process destroyed much of America’s export economy; transferred massive amounts of wealth from debtors to creditors and kick-started what would become a decades-long period of asset price inflation and growing wealth inequality in America; and gutted large swaths of the US agricultural and industrial economy, in the process devastating the livelihoods and communities of many farmers and working class Americans.

Volcker’s policies also triggered a series of costly financial crises in banking, home lending and LDC sovereign debt which were surpassed in modern US history only by the events of the 1930s and 2008. Yes, Volcker worked hard to address each of these financial crises, more or less successfully, a task for which he was well prepared as the former President of the NY Fed and before that as Deputy Secretary, International, in Nixon’s Treasury Department (during the period when Nixon took the US dollar off the gold standard, which Volcker played a role in). But we should not lose sight of the fact that each of these financial crises during the 1980s was caused, or at least triggered, in large part by Volcker’s own war on US price inflation. So yes, Volcker played an important role in putting out these various financial fires, but he also had a hand in starting them.

But even if we judge Volcker solely with regard to his battle against inflation—which was after all the top economic priority not only of the Fed, but also of the leaders of both political parties—the Volcker inflation legacy is not as simple or clear cut as we perhaps remember it today. The Greider book goes into this topic at great length, but let me mention just one specific example where our collective memory of Volcker’s inflation fighting legacy may differ from the reality, the role of ‘monetarism’ in the Volcker Fed.

Paul Volcker was not a ‘monetarist’. This may come as a big surprise to many of today’s Fed critics and Volcker devotees, but Paul Volcker was no monetarist, at least not in the Milton Friedman sense of the word. (Friedman was a close advisor of President Reagan, who considered himself a ‘monetarist’, although he likely had little detailed knowledge of what this really meant.) It is true that the Fed under Volcker very publicly shifted its monetary policy strategy away from directly managing the level of interest rates to managing the supply of money, in true monetarist fashion, which it announced at a hastily convened Saturday morning press conference over Columbus Day weekend 1979. (You can read about this here.). And in this sense it is certainly fair to say that Volcker’s Fed expressly adopted a ‘monetarist’ approach to fighting inflation, at least initially. And it is also fair to say that Volcker himself was the driving force behind this radical policy shift, but perhaps not for the reasons often attributed to him today.

As recounted in the Greider book, and confirmed by others who were on the scene at the time, it seems that Volcker’s unexpected move to monetarism may have been intended as largely a Trojan horse designed to provide the Fed with political cover for the inevitable rise in the level and volatility of interest rates which Volcker knew would result from his subsequent policy decisions. By announcing a shift in the Fed’s focus away from interest rates (fed funds) and onto the monetary aggregates (specifically M1)—a policy approach specifically endorsed and encouraged by the Reagan administration (under the influence of Milton Friedman)—Volcker was able credibly to blame others for the consequences of its own actions, in this case the fickle bond market and the politicians in Congress and the White House responsible for the rapidly growing federal deficit and debt.

To be a successful Fed chair requires many important skills and personal qualities, all of which Volcker had, but at the top of the list is understanding how to manage the various political pressures on the Fed and thereby maintain its public credibility and policy independence. And in this regard at least it seems that Volcker was indeed a master.

The Fed’s monetarist experiment under Volcker was largely a failure and was quickly abandoned. Whatever the true intent behind Volcker’s monetarist policy shift announced in October 1979, the experiment was largely a failure and was terminated after just three years, in October 1982. During much of this time, the FOMC and its staff experienced great operational difficulty defining, measuring and managing the money supply, which of course is rather critical to implementing a successful monetarist policy. As documented in Greider’s book, the FOMC was often essentially clueless as to the changing and volatile relationships between its chosen monetary target (M1) and the market level of interest rates, the supply of credit, the impact of financial deregulation and the level of real economic activity. And Volcker himself was regularly surprised by the capital markets reaction to some of the Fed’s moves, which he blamed publicly on the federal deficit and debt even though the likely culprit was really the Fed’s own disjointed and poorly understood tinkering with the money supply. And so after just three frustrating years, during which the monetary aggregates bounced all over the place causing mass confusion on Wall Street and in the business community, the Fed abandoned its monetarist experiment and reverted to its tried and tested policy of managing interest rates (fed funds) directly. Milton Friedman’s monetarist theories may have been quite sound in theory—he won a Nobel prize after all—but as implemented by the Volcker Fed they did not work very well in practice, which Friedman himself seemed at a loss to explain.

On balance, how should we think today about the Volcker legacy? This of course is for each of you to decide. On Wall Street and amongst the creditor classes, Volcker is today regarded as a hero for his hard fought victory over inflation during the 1980s. As noted above (and documented in the Greider book), there is much truth to this narrative and we should not lightly dismiss it. But Volcker’s legacy looks quite different when viewed from the perspective of the bankrupt farmers, unemployed construction workers and working class Americans who lost their livelihoods and their communities during this period of time. What Reagan Republicans today recall with misty eyes as “morning in America” looked to many at the time as an economic nightmare orchestrated by the US government explicitly for the purpose of transferring wealth from farmers and blue collar workers into the pockets of rich and powerful financiers. And to make matters worse, these controversial policy decisions were developed, made and implemented by unelected officials in the single most democratically unrepresentative and politically unresponsive branch of the US government. No, not the Supreme Court. The Fed.

I don’t know which of these competing Volcker narratives is more accurate—no doubt there is much truth to all of them—but there is no reason we need to pick one over the other and I think we should all resist the urge to do so. The world of public policy decision making is rarely black and white or cut and dried; it was not so in the 1980s Fed and it is not so today. We have many serious economic challenges now facing our country (indeed the world) and today’s inflation problem is far from the most important of them (although it may be the most urgent). But all of these challenges—climate change, political dysfunction, geopolitical risk, income and wealth inequality, and yes inflation—confront us with serious, complex and consequential problems to which there is no easy, clear or painless solution, despite what we might like to believe or what our political representatives lead us to expect.

Of course this was also the case with the more serious problem of inflation during Volcker’s time at the Fed. But Paul Volcker understood this, even if others did not. And to his credit, Volcker personally acknowledged the costs and risks associated with his policy decisions, although for tactical reasons he didn’t always choose to communicate this publicly. Which I think is more than we can say for many of our elected and appointed public officials today.

And for this reason, among others, I think we all owe Paul Volcker a large debt of gratitude for a job mostly well done and a professional life of public service very well lived.

Links:

Paul Volcker Obituary, NY Times, December 9, 2019

Volcker’s Announcement of Anti-Inflation Measures, October 1979, Federal Reserve History

Volcker Out as Fed Chair, Replaced by Greenspan, NY Times, June 3, 1987

Monetary Policy 25 Years after October 1979, Book Review St. Louis Fed Conference, 2005