In my last post, Promises Promises, I suggested that President Trump’s ill-tempered attacks on Fed Chair Powell, while outrageous, may be a bit of a sideshow to the bigger story we should all be concerned about: the impact which our growing federal deficits and debt may have on the Fed’s ability to control inflation. President Trump may or may not understand exactly what he is doing, but some of those around him surely do, most notably Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who is already hard at work implementing various forms of financial repression to support the Fed’s future monetization of the public debt.

After hitting ‘send’ on my prior post, I came across this excellent piece by Macro-Musings host David Beckworth, in which he explains the economic theory behind what I had tried to say in my last post. For those who can’t be bothered with the theory (or the math), here is how Beckworth summed up his arguments (and mine):

“The fiscal forest is burning and too many observers are fixated on the Trump trees. Yes, his showmanship and public browbeating of the Fed deserve scrutiny. But if we stop there we risk missing the deeper, more consequential story.

That story is about arithmetic. It is about the inescapable logic of the consolidated government budget constraint. When interest payments on the debt rise and primary surpluses are politically off the table, something else has to give. That something is more debt, more money creation, or both. And when the central bank is forced to accommodate fiscal needs, it loses its economic independence. When that goes, the political, legal, and financial independence of the Fed will not be far behind.

This is not a partisan problem. It is not just about Trump. It is the result of decades of fiscal drift, demographic pressures, political gridlock, and wishful thinking. The constraint does not care who sits in the Oval Office or chairs the FOMC. It cares only about balance between promises and resources, between obligations and tools.

If we want to preserve central bank independence, we must first acknowledge the quiet but growing force that undermines it: fiscal unsustainability. Until then, everything else is just noise.”

Fed independence should be of critical importance not only to economic policy wonks, but to all of us. And particularly to those who screamed the loudest during our recent (but temporary) bout of high inflation in the wake of the covid pandemic. Economic pundits and policymakers continue to debate who and what was responsible for this short period of rapidly increasing prices. Was it covid-induced supply shocks, excess fiscal stimulus from the Trump and Biden administrations, too-loose Fed monetary policy, or something else entirely? But while these are interesting and important questions, a far larger concern should be the unsustainable growth in federal deficits and the debt over past decades and our collective inability or refusal to deal with it directly through the political process. Until we get a handle on this, we had all better get used to higher future inflation and its consequences.

The simple truth is that over the past sixty years, but particularly over the past twenty-five years, presidents and congresses from both political parties have seen fit to make unfunded commitments for large amounts of future federal spending while refusing to raise the tax revenue necessary to pay for all of it, leaving us with ever greater amounts of federal debt and in the process increasing pressure on the Fed to inflate away some of the pain by printing money.

Most federal spending over the past decades has been for elective purposes. The money has been spent on social programs, defense, subsidies to politically favored interest groups, and expansion of the administrative state. We have put a man on the moon and funded many incredible scientific discoveries. We have built a national highway, the air traffic system and the internet. We have largely eradicated poverty in this country (by world standards) and we have provided health care and educational opportunities to those who could not afford to pay for it themselves. These are all good things, of course, but they did not come cheap and they all added to government expenditures.

We have also fought several costly foreign wars; we have experienced economic crises which increased federal expenditures and reduced tax revenues; we have had to clean up after increasingly frequent and damaging natural disasters; and we have been hit with one particularly nasty pandemic which shut down a large part of the economy for the better part of a year. These too have added significantly to federal deficits and the debt, most notably covid, which may have cost the federal government something like $6-7 trillion over a very short period of time.

With the passage of time, our population has aged, increasing the current cost of so-called ‘entitlement’ programs, which were established when life expectancy (and the cost of health care) was far less than it is today, and when we had many more workers contributing to the support of those who for whatever reason were no longer able or expected to work or who could not provide adequately for themselves and their families. Notwithstanding these demographic trends, however, we have continued to expand many of our social benefit programs far beyond their initial design, to the point where our “social safety net” now covers virtually the entire US population.

All of this government largess costs money, not just billions but trillions of dollars. And while most of this spending has been funded through tax revenues, a large and growing share of it has not. Over the past sixty years, the American people have demanded more and more from our federal government, but we have not always been willing to tax ourselves to pay for it, preferring instead to shift the tax burden to future generations.

There are only three ways to pay for government expenditures: by taxation, borrowing and/or money creation (‘printing money’). By definition, fiscal deficits result when tax and other revenues do not cover the full cost of current government expenditures. These shortfalls are typically financed through increased government borrowing, with interest payable on the growing amounts of federal debt. From time to time, however, the federal government has looked to the Fed for additional support in the form of reduced interest rates and/or the purchase by the Fed of large quantities of government debt, paid for with newly created reserves (ie ‘printing money’). This has most often occurred in times of national emergency, most notably during the two World Wars but also more recently during the covid pandemic, the latter of which cost the federal government in real terms about as much (possibly more) than did World War II (although far less as a percent of US GDP).

The result of all these unfunded expenditures has been large and growing federal deficits and debt. But how much money are we talking about? And how did we get to this point? The answers may surprise some readers, so let’s dig into the numbers a bit, looking at some of the high-level trends, leaving for future posts a more detailed discussion of the federal budget and the consequences of future inflation.

As indicated in the chart above, the federal government in 2025 is expected to run a deficit of approximately $1.9 trillion, representing the difference between annual federal spending of roughly $7 trillion (23% of GDP) and federal revenue (mostly from taxes) of a bit over $5 trillion (17% of GDP). And while it is sometimes hard to get our heads around numbers this large—$1 trillion equals $1,000 billion—it might help to consider that the current federal deficit of $1.9 trillion equates to a bit over $14,000 per US household, a not inconsiderable sum relative to the average (mean) US household income of ca $115,0000. This $14,000 per household deficit equals the difference between $38,000 (per household) of government revenues (mostly taxes) compared to $50,000 (per household) of government spending.

At about 6.3% of GDP, the current US fiscal deficit is over two and a-half times larger than it was just ten years ago (2.4% of GDP), and an even bigger change from twenty-five years ago, when the US federal government ran a budget surplus equivalent to 2.5% of GDP. (See the FRED data here.) The annual federal deficit has increased by the equivalent of 8.8% of GDP over a period of not quite twenty-five years, from the end of the Clinton administration to the present.

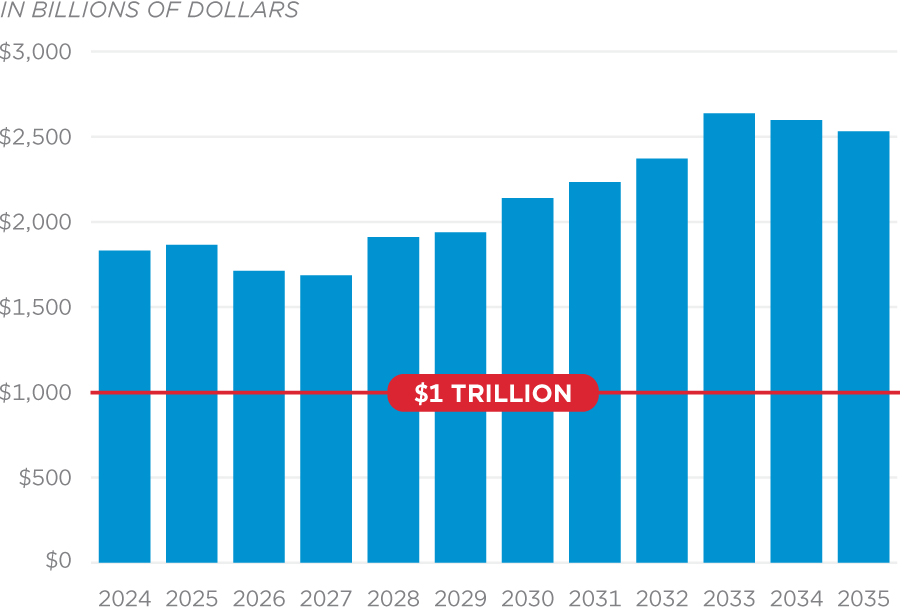

The picture is not expected to improve going forward, as shown in the chart above. Per CBO forecasts from January, federal deficits were estimated to peak in 2033 at around $2.65 trillion, an increase of roughly 40% from current levels. And this was before the fiscal impact of President Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill, which the CBO estimates will over the coming decade add another $3.4 trillion to cumulative (not annual) US primary deficits and more like $4 trillion including increased interest expense, which is already running at ca $1 trillion a year (and growing).

Over the past sixty years, federal expenditures have increased from 25% to 35% of GDP, in large part as a result of the growth in so-called ‘entitlement’ spending under both Republican and Democratic administrations. (During covid, current expenditures temporarily peaked at over 50% of GDP.) On the other hand federal receipts (mostly from taxes) have stayed broadly flat as share of GDP, at around 18%. In a very real sense, our current fiscal situation is not simply the result of increased government expenditures, but rather of increased expenditures relative to flat tax revenues.

The consequence has been a massive increase in the federal debt, which is now at roughly $36 trillion on a gross basis, and $30 trillion if we exclude intra-governmental debt obligations. The vast majority (over 80%) of this debt has been incurred over the past twenty-five years, and one-third of it has been incurred in just the past five years, in large part as a result of covid.

For some historical comparison, consider that when LBJ took office in 1963, the US federal debt was around $300 billion, less than 1% of what it is today. When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the debt was $1 trillion, less than 3% of what it is today. When George W. Bush took office in 2001, it was $5.8 trillion, 16% of what it is today. When Barack Obama took office in 2009, it was $11 trillion, one-third of what it is today. And when Donald Trump first took office, it was $20 trillion, just over half of what it is today.

These numbers are a bit misleading, of course, due to the impact of inflation over this long period of time. But the federal debt has also grown quite significantly in real (inflation-adjusted) as well as nominal terms. Converting the nominal historical debt levels into 2025 dollars, that $300 billion of federal debt when LBJ took office would equate to $3 trillion today. The $5.8 billion when GW Bush took office would equate to $10 trillion today. And the $11 trillion when Obama took office would equate to $17 trillion today. In real terms, close to 30% of our current federal debt has been incurred just during the past eight years.

Another way to look at this is to consider the growth in the federal debt not just in absolute nominal or real terms, but relative to the size of the US economy. As a share of GDP, the federal debt actually fell markedly during much of the 1960s and ‘70s, but it exploded after Ronald Reagan took office, more than doubling by the time Bill Clinton took over. And it has doubled again since then, to its current level of 120% of GDP.

The gross federal debt currently stands at $36 trillion, but it will likely increase by another $8 trillion or so over the next three and a-half years, with annual deficits forecast to continue at nearly 6% of GDP. Unless something changes dramatically over this period—which seems unlikely given the recent passage into law of Trump’s controversial ‘Big Beautiful Bill’—the federal deficits incurred under President Trump, the self-designated “king of debt”, will have added approximately twice as much to the federal debt ($16 trillion) as those of any other president in US history. In fact, over one-third of our entire federal debt (in nominal terms) will have been incurred during President Trump’s two terms in office.

When we reflect upon these numbers, we can perhaps understand better why the Trump administration is now putting so much pressure on the Fed to slash interest rates. In a world where the President and Congress are not prepared to slash federal deficits, but don’t like paying increased interest expense on the growing federal debt, the only alternative left is to pressure the Fed into monetizing the federal debt, something which Republicans have (rightly) railed against for decades, although only it seems when the Democrats are in power.

And this is why the Trump administration’s war on the Fed is such a big deal. It is a canary in the financial coal mine, giving us warning of the dangers which lie ahead.

Links

An excellent article. The trajectory is catastrophically bad and both parties are responsible. We’ve seen many examples of the consequences to countries that have let government indebtedness exceed sustainable levels - and these consequences sometimes occurring with indebtedness metrics (debt / GDP, deficit / GDP) that were lower (less adverse) than are the US’s. The US$ reserve currency status, perception of safety in volatile periods and other characteristics give the US some leeway, but we’re at or maybe beyond an inflection point.