The Boeing Company is an American manufacturing icon. Founded in 1916, Boeing built the legendary 747 passenger jet and the B-52 World War II bomber, helped NASA land the first man on the moon, and has supplied the US federal government with Air Force One jets and Apache helicopters. Boeing and its European competitor Airbus dominate the global commercial airliner manufacturing business, and Boeing is the fourth largest defense contractor in the world. Boeing is the largest exporter in America; it employs over 170,000 people; and it generated over $75 billion of revenues in its last full fiscal year. And for most of its corporate history, Boeing was one of America’s most admired companies. But no longer.

The past several years have not been kind to Boeing. In late 2018 and early 2019, two Boeing 737 MAX 8 jets crashed when the planes’ flight control software failed, causing the deaths of 347 people. The accidents resulted in the worldwide grounding of Boeing’s entire 737 fleet for 20-months, the cancellation of customer orders for 1,200 Boeing planes, and the filing of civil and criminal charges against the company. In 2020 the covid pandemic shut down airline travel worldwide and created chaos in the global aviation industry. The launch of Boeing’s newest line of wide-body jets, the 777X, was originally scheduled for release in 2020 but is now five years behind schedule. Boeing’s defense and space unit has lost billions of dollars on government contracts and has experienced extensive development delays and technical problems with its Starliner space capsule, which this past summer was forced to return to earth empty-handed after leaving two US astronauts stranded at the International Space Station. (They will be brought home in February by a Boeing competitor, Elon Musk’s SpaceX.)

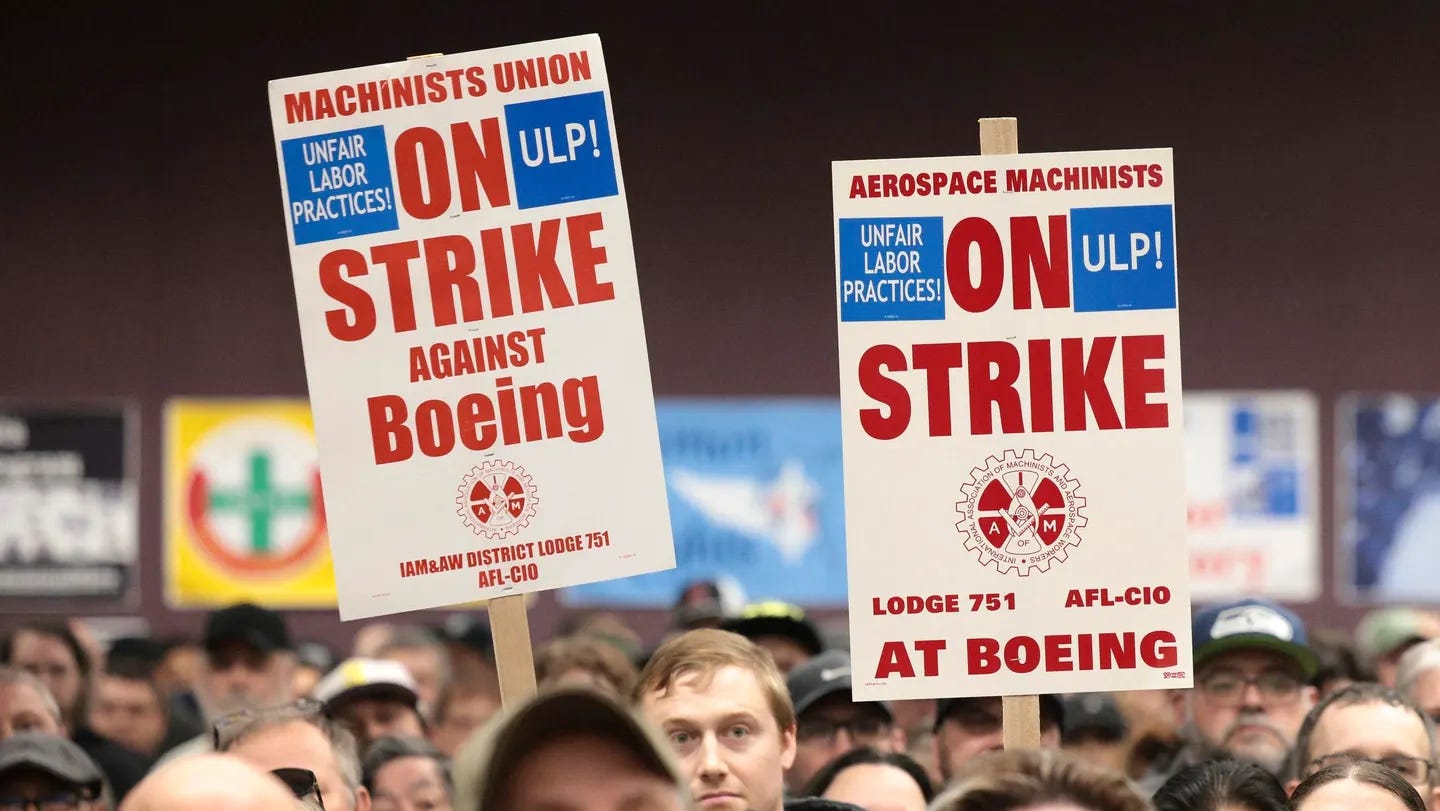

In January of this year, a Boeing 737 MAX 9 plane flown by Alaska Airlines was forced to make an emergency landing after an improperly installed fuselage panel blew off the plane at an altitude of 16,000 feet, narrowly averting disaster for the 177 passengers and crew on board. In March, the National Transportation Safety Board issued its preliminary report on the Alaska Airlines accident and the Justice Department opened its second MAX-related criminal investigation of Boeing. That same month, increased pressure on the Boeing board of directors triggered the resignation of its CEO along with the head of the commercial aircraft business and the chairman of the board. And in mid-September, over 30,000 Boeing machinists elected to go on strike, a strike which has now been settled but will have cost Boeing an estimated $1.5 billion ($30 million per day)

Over the past five years, Boeing has had three CEOs. It has reported over $26 billion in consolidated loss from operations, including a $6.8 billion loss in the most recent quarter, and has not earned a profit since 2019. In 2020, the company stopped paying dividends and making share buybacks, after distributing to its shareholders a cumulative $64 billion over the prior seven years. The company’s share price has fallen over 50% during a period when the stock market has roughly doubled, at a cost to the Boeing shareholders of more than $300 billion. By early October, all three credit rating agencies had placed Boeing on their watch list for possible downgrade to non-investment grade (junk) status, which the company hopes to have preempted with the recent issuance of $21 billion in new equity. And while the company’s backlog of unfilled orders now stands at roughly $500 billion, it remains highly uncertain how much of this Boeing will be able to convert into sales, profits and value for its shareholders.

Suffice it to say that Boeing has seen better days.

But why is Boeing having so many problems? Is this just a case of a “perfect storm” of random and unrelated events which Boeing could not reasonably have anticipated or prevented? Or is there something else more fundamental and pernicious going on at Boeing? And if so, what is it?

Let’s explore.

Boeing at a Glance. As noted, Boeing is one of the world’s two largest commercial aircraft manufacturers and the fourth largest defense contractor, and it is the United States’ largest exporter. Boeing employs over 170,000 employees across its various lines of business, including the 33,000 unionized machinists in the commercial airplane business who went on strike in mid-September and have now returned to work. For most of its corporate history, Boeing’s corporate headquarters was in Seattle WA, near the site of its largest commercial airplane assembly plant. In 2001, however, it moved its HQ to Chicago for the express purpose of distancing its corporate executive team from the west coast commercial airplane operations. In 2017 Boeing again moved its corporate headquarter, this time to Arlington VA, where its defense, space and security business is also based. Boeing’s largest commercial airplane assembly plants are now located in Seattle (unionized) and Charleston SC (non-union).

In its latest full fiscal year (2023), Boeing reported over $75 billion in total revenues, down from $100 billion in 2018. Boeing is organized into three financial reporting segments: commercial airplanes; defense, space and security; and global services. Revenues in the commercial airplane business were close to $60 billion in 2018 but fell to $16 billion in 2020, and were $18 billion in the latest nine-month reporting period. Of Boeing’s three business units, the only one which has been consistently profitable in recent years has been global services. The commercial airplane business has reported over $36 billion in cumulative losses since 2018 and Boeing itself has not reported positive consolidated net income in any quarter since 2019.

As of September 30, 2024, Boeing had total assets of $138 billion, of which 60% ($83 billion) consisted of inventory, financed in part with $56 billion of customer advance payments and progress billings. Boeing had $58 billion of total financial debt, $8 billion of pension and retiree health liabilities, and shareholders equity of negative $24 billion (prior to its recent $21 billion share issuance). Boeing’s contractual backlog of unfilled customer orders stood at $500 billion.

Boeing’s senior unsecured debt is currently rated at the bottom level of investment grade (BBB-) by all three major rating agencies, which by October had placed the debt on watchlist for possible downgrade to non-investment grade (junk) status. (This was before the completion of Boeing’s recent capital increase and the termination of the IAM strike).

Boeing’s liquidity position is currently strong, having just raised $21 billion from the sale of newly issued common stock and mandatorily convertible preferred shares. Pro forma for that offering, Boeing is sitting on over $30 billion of cash plus $20 billion of committed but undrawn bank credit. Financial debt coming due in the next twelve months is less than $5 billion, with another $8 billion or so coming due the following year. Of Boeing’s $58 billion of total debt, half of it carries an annual interest rate of less than 4%, well below current market yields of 6% or so.

Boeing shares currently trade at a market price of around $150 a share, down 40% year to date but largely unchanged since completion of the capital increase and settlement of the IAM strike. (Boeing’s share price fell 6% in the days prior to completion of the upsized offering.) At its current share price, Boing has a market capitalization of roughly $120 billion (adjusted for the recent issuance of 112 million new common shares). At this price, Boeing shares are trading at a P/E multiple of roughly 11x Boeing’s historical peak net income of $10.5 billion reported in 2018, the last full year in which Boeing generated positive net income.

Now, having set the stage with a bit of an overview of Boeing, and its recent travails, let’s try to understand how and why Boeing may have gone off course. And let’s begin by asking a fundamental question which too often goes overlooked in the world of corporate governance and finance.

What is the purpose of a business corporation? In my Corporate Financial Strategy course, I begin the first day of class with this question for my students: “What is the purpose of a business corporation?” Perhaps because I teach in a business school setting and my students are almost all (undergraduate) finance majors, they generally answer with some version of this initial response: “The purpose of a business corporation is to make money for its shareholders.” This is a widely held view in the world of finance, and perhaps among many readers of this blog. But in my view this perspective is fundamentally misguided, or at least misunderstood, and this misunderstanding has occasionally had a pernicious effect on the governance of American businesses, including Boeing.

The purpose of a business corporation is not to make money for shareholders; it is to produce products and services of a quality that customers want to buy, at a cost (price) that customers find attractive, and to do so in a way that is sustainable over time. Profit generation is one desired (and desirable) output of this process, without which the provision of valuable products and services would not likely be sustainable (or financeable) over time. But while making money may be the primary motivation for the shareholders of a business corporation, who must be incentivized to put their capital at risk, this should not be the sole or even the primary purpose of the business corporation itself.

My views in this regard have been heavily influenced by a short book which I assign to all my corporate finance students and which I recommend to those of you who are not already familiar with it: Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance, written by a team of McKinsey executives (Tim Koller et al, 2010). [Don’t confuse Value with Koller’s better known book Valuation, which many of you will have read and may well use in your professional work.] In Koller’s view, shareholder value (by which he means economic value) should be the primary metric used to guide most corporate decision making; but while profitability and return on capital are critical components of shareholder value, these are generally outputs and not drivers of the value creation process per se. For Koller, shareholder value creation is fundamentally driven by some combination of corporate strategy, product quality and operational performance—what I will call fundamental business performance—and not by the sort of financial engineering promoted on Wall Street and practiced in some corporate boardrooms, including Boeing’s.

Quality is Job 1. Product quality is rarely the sole determinant of any company’s success, and it may not even be the primary one. But in some industries the quality and reliability of a manufacturer’s product is deemed to be critical to commercial success, at least in certain functional areas (like safety). And the aviation business appears to be one of them.

When Boeing’s two 737 MAX 8 jets crashed in 2018 and 2019, the cause of the accident was attributed to the failure of Boeing’s proprietary flight control system. This system was designed by Boeing to have only a single point of failure, with no backup control for this mission-critical function, and when the flight control system failed so disastrously it called into question the safety and reliability of Boeing’s entire fleet of planes. And while the recent near-miss at Alaska Air was in some respects less troubling, as more of a one-off event than a system-wide failure, Boeing’s customers and regulators were rightly shocked by the apparent incompetence of the assembly work performed at Boeing (or at one of its sub-contractors under Boeing supervision). After all, if a company like Boing cannot properly bolt a door panel onto a plane fuselage, it really has no business making (or assembling) planes in the first place.

During the early 1980s, the Ford Motor Company ran ads with the slogan “Quality is Job 1”, to publicize a change of corporate strategy adopted in response to the crippling onslaught of competition from the Japanese automakers, who offered US automobile buyers a better-quality product at lower price than was then being produced in Detroit. And although the context is quite different, the parallels between Ford in the 1980s and Boeing today are interesting. Like Ford, Boeing seems over the years to have let its design and manufacturing standards slip, and it must once again get serious about product quality if it hopes ever to regain the confidence of its customers, restore its reputation and return to profitability.

To accomplish this, however, Boeing (like Ford) will have to make some fundamental changes in its company culture, returning to its roots as a company run by aviation engineers with a focus on product quality and reliability, and not by financial engineers concerned primarily with profit margins, earnings per share and stock price.

From engineering to financial engineering. Boeing was historically a company run by aerospace engineers who focused obsessively on engineering excellence and product quality. Perhaps Boeing did not always pay as much attention as it could or should have to generating profits and financial returns, to the dismay of its shareholders, but for most of its history Boeing did have a reputation for making great planes. Not every company needs to produce its products with six sigma (zero defects) design and manufacturing processes, which is expensive and which not all customers will pay for, but some companies do think this is necessary and historically Boeing was one of them.

Over the years, however, this seems to have become less and less true. I don’t know who coined the old phrase “If it’s not Boeing, I’m not going”, but it is hard to imagine this being said today, other than in jest. Instead, one is more likely to hear something along the lines of what Senator Jon Tester relayed to former Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenberg after the Alaska Airlines fiasco: “If it’s a Boeing, I’d rather walk.” But even if Senator Tester’s statement was a bit hyperbolic, this widely held view of the deteriorating quality and reliability of Boeing’s planes in recent years has not been good for the company’s reputation or for its business.

By many accounts, including those from company insiders, Boeing seems over the past twenty years to have relaxed its relentless focus on engineering excellence and product quality to pursue a strategy of maximizing profitability and shareholder returns. Many observers date the origins of this strategic shift to Boeing’s 1997 acquisition of its competitor McDonnell Douglas, another major aerospace and defense contractor with a strong focus on financial performance. Although the transaction was billed as the acquisition of McDonnell Douglas by Boeing, it was at the time regarded by many observers as in effect a reverse takeover of Boeing by McDonnell Douglas. The deal was financed in large part with Boeing’s own money, a large premium was paid (in Boeing stock) to the shareholders of McDonnell Douglas, and key management and board positions at the new company were awarded to McDonnell Douglas executives and directors.

The acquisition of McDonnell Douglas has impacted Boeing in many ways, but perhaps the most significant and long-lasting impact of the transaction has been on Boeing’s culture. As noted, Boeing was historically a company run by engineers with a deep-rooted culture of engineering and manufacturing excellence, a source of pride which ran from the company’s executive offices down to the shop floor. In contrast, McDonnell Douglas was perceived by many as a company run by MBAs more concerned with cost control, return on capital and share price than with engineering excellence or product quality and reliability. And when senior McDonnell Douglas executives ended up in top executive jobs following the merger, they took it upon themselves to transform the way Boeing did business, with a shift in focus from aviation engineering to financial engineering.

According to Harry Stonecipher, the McDonnell Douglas CEO and Boeing board member who came out of his post-merger retirement to take the top job at Boeing in 2003, following a government procurement scandal at the company, this was the plan all along. “When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so it's run like a business rather than a great engineering firm”. This of course meant a much greater focus on profitability and return on capital, even at some cost to engineering excellence and product quality. As Stonecipher said, “the reason people invest in a company is because they want to make money.”

And for the next fifteen years or so, ‘making money’ is exactly what Stonecipher and his successors set out to do, quite successfully.

Stonecipher himself was forced out of Boeing in 2005, after the board discovered that he had been having an affair with a company employee, but his prioritization of corporate profitability was shared by his successor James McNerney, an American-studies major from Yale with an MBA from Harvard. McNerney was the first Boeing CEO without a background in aviation, and his formative business experiences were at P&G, McKinsey and Jack Welch’s GE, all companies known for their promotion of shareholder value as the lodestar of corporate strategy and governance.

McNerney was the CEO of Boeing from 2005-15 and it was largely under his leadership that Boeing became the company we know today. During McNerney’s tenure, Boeing took the decision to open a non-union commercial assembly plant in South Carolina to produce the new 787 Dreamliner, as well as the decision to retrofit Boeing’s thirty-five year old line of 737 jets rather than to design and build a new more modern model of plane in the face of a competitive new product offering by Airbus. And although the decision to “off load” Boeing’s fuselage assembly operations to the newly formed Spirit AeroSystems was taken before McNerney joined the company, the transaction rationale was consistent with his own strategic mindset, with an increased focus on “capital light” manufacturing.

For quite a few years, the Boeing shareholders were richly rewarded for the efforts of McNerney and his successor, Dennis Muilenburg (2015-2019). Revenues grew strongly, profit margins increased, earnings per share and return on equity were enhanced by share buybacks, stockholders received big dividend checks, and the Boeing share price increased substantially (well in excess of market returns). Boeing had by all accounts become a corporate financial success story, no doubt with high fives regularly exchanged all around the Boeing board room, and rightly so. Or so it seemed at the time.

‘Capital light’ manufacturing. In thinking about the various issues confronting Boeing today, it helps to keep in mind that while we refer to Boeing as a “manufacturer” of commercial aircraft, what we really mean is that Boeing “assembles” commercial aircraft, with much of the primary manufacturing (and sometimes the design) responsibility for its component parts outsourced to third parties. This is not unique to Boeing—Airbus operates in much the same way, as do many other large and successful manufacturing companies—and the use of outsourcing is not a particularly new development at Boeing or elsewhere.

Boeing has been building 737 jets for almost six decades now, with over 10,000 planes produced to date, and most of the component parts of these planes have been manufactured by companies other than Boeing. Each 737 MAX jet produced today contains something like 500,000 parts which are produced by 600 or so suppliers, leaving Boeing primarily responsible for assembly of the planes and for supervising the design, manufacturing and quality control processes at its suppliers. Importantly, it is not just the “small parts” of planes which Boeing has outsourced to third party manufacturers; outsourced components also include mission-critical items such as fuselages, landing gear and elements of the flight control system. And in the case of the Dreamliner 787, much of the primary design work for the new plane was outsourced as well.

It would be unfair to blame outsourcing for all of Boeing’s current problems, but it does appear that Boeing itself may be having second thoughts about the wisdom of outsourcing of at least certain of its core operations, for example fuselage manufacturing. Since 2005, Boeing fuselages have been manufactured by Spirit AeroSystens, initially a private equity backed company formed for the purpose of acquiring Boeing’s own fuselage manufacturing operations, headquartered in Wichita KS. By selling its fuselage manufacturing operations to the newly formed but independently owned Spirit, Boeing reduced the amount of its own (on balance sheet) capital investment in these operations and thereby increased the related return on capital reported by Boeing to its shareholders. As a result of the sale, however, Boeing also turned over primary control of the fuselage manufacturing process to Spirit, while maintaining inspectors on site to monitor the quality of the work being done on its behalf.

At the time, this no doubt seemed like a sensible trade-off for Boeing: enhanced financial returns in exchange for less direct (but still significant) control over the fuselage manufacturing process. And while Boeing may well have been happy with this relationship for much of the past twenty years, it’s perception seems to have changed in the wake of the Alaska Air mishap. And so in July of this year, Boeing agreed to acquire Spirit in a transaction scheduled to close in mid-2025, at which point Boeing will have brought back in-house and on-balance sheet the fuselage manufacturing operations which it was so eager to “off-load” (Boeing’s characterization) twenty years ago.

Boeing’s Share Buybacks. Boeing’s recent problems have not all been operational, they have also been financial, and again some of this has been self-inflicted. Over the past five years, Boeing has lost a lot of money, burned a lot of cash and incurred a lot of debt. This has pushed Boeing’s credit ratings to the bottom rung of investment grade, which is not the most obviously prudent or sustainable strategy for a company with $58 billion of financial debt. And so when Boeing’s unionized machinists went on strike in mid-September, the credit rating agencies put the company’s debt on their watch lists for possible downgrade to ‘junk’ status, an event which had it occurred would have made Boeing’s future debt financing (and refinancing) not only more costly but less certain as well.

Boeing’s financial risk has been reduced substantially over the past few weeks, with settlement of the IAM strike and with Boeing’s successful $21 billion capital increase. The company is now sitting on something like $50 billion of liquidity—$30 billion of cash plus $20 billion of committed but undrawn bank credit—as well as a $500 billion contractual backlog. But despite this significant recent improvement in its financial position, one has to wonder how it came to be that Boeing let itself get into the financially vulnerable position it did, with $58 billion of debt and negative shareholders equity, while operating in a notoriously cyclical, volatile and uncertain business.

Part of the answer of course is that Boeing unexpectedly lost a lot of money over the past five years—$26 billion at the corporate (consolidated) level—but there is more to the story than this. It is also the case that over the past two decades (pre-covid), Boeing made a conscious strategic financial policy decision to return to its shareholders an exceptionally large share of its earned income. From 1998-2019 Boeing distributed to shareholders as dividends and share buybacks over 120% of reported profits, including $63 billion during the years 2013-2019. And this decision to distribute large amounts of cash to shareholders—rather than to reinvest in the business, pay down debt or hold onto more cash for a rainy day—goes a long way to explaining Boeing’s current financial position. This does not mean the decision was wrong, of course, but the distributions did reduce Boeing’s capital and liquidity by a very large amount, and perhaps more than was prudent (at least in hindsight).

And so, when the proverbial you-know-what hit the fan beginning in 2019 (with the 737 MAX crashes and then covid), Boeing found itself in a precarious financial position, with a reduced capital base available to absorb any future losses. Of course, Boeing did not at that time expect to lose $36 billion in its commercial airplane business over the next few years, but then no one ever expects the unexpected. No one expected the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001; no one expected the global financial crisis in 2008; and no one expected the global covid pandemic in 2020. But although unexpected, all of these things happened, and when they did the financial losses experienced in certain industries (including the aerospace industry) were catastrophic, or would have been but for large amounts of direct and indirect government aid.

The reason prudent companies in particularly vulnerable (or critical) industries choose to hold significant amounts of shareholders equity (paid-in capital and retained earnings) is exactly this: to absorb unexpected future losses and reduce the likelihood of corporate insolvency or a major disruption of their business. These companies understand that “stuff happens”, as Donald Rumsfeld might have said. (In fact he did say this, after the US invasion of Iraq under his supervision generated some rather unexpected and unwelcome surprises.) And in the world of corporate finance, when bad stuff happens it helps to have sufficient capital (and cash) to absorb any resulting losses.

The more uncertain, cyclical and volatile a company’s business is—or the more important its uninterrupted operations are to the proper functioning of the economy—the more equity one might reasonably expect a prudent company to hold. But this is not always true, and in certain industries (like aerospace), rational boards of directors often choose to operate with high amounts of financial leverage. And when times are good, they make large shareholder distributions rather than paying down debt, despite the associated risks. But why?

The answer, I think lies in how one thinks about risk and return, and specifically the risks and returns associated with high financial leverage and the use of OPM (Other People’s Money). Did the Boeing board increase the future financial risk to its stockholders by paying large dividends, buying back shares and funding these distributions with increased debt? Well, yes and no. The riskiness of Boeing’s equity capital (common stock) certainly increased with the greater amount of financial leverage employed by the company. But as a result of the large shareholder distributions, the Boeing shareholders themselves had much less of their own money invested in the company, and therefore at risk.

As things turned out, the Boeing shareholders got paid very well for accepting the risks associated with higher leverage, at least initially. From 2013-2018, as the company’s leverage increased with $76 billion of shareholder distributions, Boeing’s shareholders earned an annual compound rate of return of roughly 30%, more than double that earned by investors in the S&P (12.8%).

Boeing’s shareholder returns have been quite different in the past five years, however, as Boeing terminated all shareholder distributions in 2020 and its share price fell over 50% while the broader stock market doubled in value. But because of the company’s shareholder distribution policies over the prior two decades, Boeing shareholders lost a lot less money than would otherwise have been the case.

There is one more aspect to this narrative which I should mention. And this is the matter of moral hazard, the phenomenon by which the taking of financial risk increases when one’s losses are insured, or when one expects that some third party (eg creditors or the government) will pick up a share of one’s losses. We saw the operation of moral hazard in spades during the run-up to the global financial crisis, as banks levered up and ran their businesses with as little as 2-3% equity capital. We have seen this in the airline and auto industries, which have historically operated with surprisingly small amounts of equity capital. And we may well have seen it at Boeing.

Had Boeing come close to financial insolvency at any point in its history, it is unthinkable that the US government would have let it fail. Boeing is simply too big and too important to fail, as was the airline industry in 2001 and as were the banks (and the auto industry) in 2008. And it is quite possible, even likely perhaps, that the Boeing board recognized this when it authorized the substantial shareholder distributions made in the years following the McDonnell Douglas merger.

And so moral hazard provides one more reason why it may be rational for companies like Boeing to operate with such high amounts of financial leverage. When times are good, their shareholders benefit handsomely with levered equity returns. When times are bad, their shareholders lose big but with less money at risk. And when times are truly horrid, the company’s creditors or Uncle Sam come riding to the rescue. It makes perfect sense, at least from a shareholder perspective, if not perhaps for those who end up picking up the tab.

But is this how we want companies like Boeing to be run?

The challenges facing Boeing’s new CEO. The magnitude of the challenges currently facing Boeing are not lost on Boeing’s new CEO Kelly Ortberg, an aerospace and defense industry veteran appointed in July of this year, following the Alaska Air fiasco. Ortberg recently addressed the challenges facing Boeing in a statement issued in conjunction with the release of third-quarter results. In that statement, Ortberg identified various specific issues in need of prompt attention, beginning with settlement of the IAM strike and a reduction in financial leverage to retain Boeing’s investment grade ratings. He also mentioned product safety and quality, risk management and execution on major new product programs, supply chain management, workforce reductions and the need to develop a new plane. But the two words most frequently mentioned in Ortberg’s statement were “values” and “culture”, terms which go to the root of Boeing’s recent problems but also of course to its past successes.

Ortberg acknowledged that tone is set at the top of an organization like Boeing, and his appointment as CEO is a good first step in rebasing Boeing’s value priorities and repositioning its cultural compass. And Ortberg has begun to make some progress ticking items off his ‘to do’ list. The IAM strike has now been settled, albeit at an estimated cost to the company of over $1.5 billion ($30 million a day) and with a big multi-year pay rise for the machinists. Boeing has successfully raised $21 billion in new equity; it is sitting on $50 billion or so of financial liquidity; and the credit rating agencies will likely soon confirm Boeing’s investment grade (BBB-) debt ratings. Boeing has a contractual backlog of $500 billion, and its customers, employees and regulators all want it to be successful. With the Boeing stock price holding broadly stable at around $150 in the wake of a large dilutive capital increase, investors appear to be in a supportive but “wait and see” mode, which seems appropriate.

This is all good news, of course, but it is only now that the hard work of rebuilding Boeing’s culture will really begin. This will take a long time to achieve and success is far from assured. But given the important role which Boeing plays in the US and global economy, we should all be rooting for it to succeed. And let’s hope it will.

Links

What Went So Wrong with Boeing? WSJ. October 25, 2024

Boeing Explores Sale of Space Business. WSJ, October 25, 2024

Boeing’s Strike is Still On. It’s Strained Balance Sheet Makes Matters Worse. WSJ. October 24, 2024

Boeing Warns on Cash Burn, Awaits Strike Vote. WSJ, October 23, 2024

Boeing’s CEO is Shrinking the Jet Make to Stop its Crisis from Spiraling. WSJ, October 20, 2024

Boeing, Still Recovering from Max 8 Crash, Faces New Crisis, NY Times, February 5, 2024

What Really Brought Down the Boeing 737 Max? NY Times, September 18, 2019

Boeing’s 737 MAX is a Saga of Capitalism Gone Awry. NY Times, November 24, 2020

“I Honestly Don’t Trust Many People at Boeing: A Broken Culture Exposed. NY Times, January 10, 2020

The Roots of Boeing’s 737 Max Crisis. NYTimes, July 27, 2019

Boeing and the Dark Age of American Manufacturing. The Atlantic, April 20, 2024

What’s Gone Wrong at Boeing, The Atlantic, January 15, 2024

The Long-Forgotten Flight that Sent Boeing Off Course. The Atlantic, November 20, 2019

Boeing’s Fatal Flaw, PBS Frontline, Part One. March 12, 2024

Boeing’s Fatal Flaw, PBS Frontline, Part Two. September 14, 2021

Great read PT! I toured the Boeing factory in WA 6 years ago, highly revered company.